Re'eh, Reeh, R'eih, or Ree (ראה — Hebrew for “see,” the first word in the parshah) is the 47th weekly Torah portion (parshah) in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading and the fourth in the book of Deuteronomy. It constitutes Deuteronomy 11:26–16:17. Jews in the Diaspora generally read it in August or early September.

Jews also read part of the parshah, Deuteronomy 14:22–16:17, as the Torah reading on Shemini Atzeret.

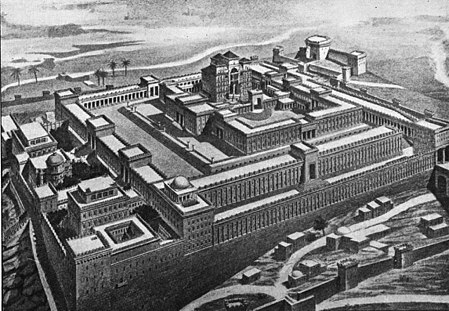

a reconstruction of Solomon’s Temple in Jerusalem, the site that God would choose as God's habitation, within the meaning of Deuteronomy 12

Summary[]

Mount Gerizim

Blessing and curse[]

Moses told the Israelites that he set before them blessing and curse: blessing if they obeyed God's commandments and curse if they did not obey but turned away to follow other gods. (Deuteronomy 11:26–28.) Moses directed that when God brought them into the land, they were to pronounce the blessings at Mount Gerizim and the curses at Mount Ebal. (Deuteronomy 11:29.)

Centralized worship[]

Moses instructed the Israelites in the laws that they were to observe in the land: They were to destroy all the sites at which the residents worshiped their gods, tear down their altars, smash their pillars, put their sacred posts to the fire, and cut down the images of their gods. (Deuteronomy 12:1–3.) They were not to worship God as the land's residents had worshiped their gods, but to look only to the site that God would choose as God's habitation to establish God's name. (Deuteronomy 12:4–5.) There they were to bring their burnt offerings and other sacrifices, tithes and contributions, offerings, and the firstlings of their herds and flocks. (Deuteronomy 12:6.) There, together with their households, they were to feast before God, happy in all God's blessings. (Deuteronomy 12:7.) Moses warned them not to sacrifice burnt offerings in any place, but only in the place that God would choose. (Deuteronomy 12:13–14.) But whenever they desired, they could slaughter and eat meat in any of their settlements, so long as they did not partake of the blood, which they were to pour on the ground. (Deuteronomy 12:15–16.) They were not, however, to consume in their settlements their tithes, firstlings, vow offerings, freewill offerings, or contributions; these they were to consume along with their children, slaves, and their local Levites before God in the place that God would choose. (Deuteronomy 12:17–18.)

14th-12th century B.C.E. bronze figurine of the Canaanite god Baal, found in Ras Shamra (ancient Ugarit), now at the Louvre

7th century B.C.E. alabaster Phoenician figure probably of the Canaanite goddess Astarte, now at the National Archaeological Museum of Spain

Not following other gods[]

Moses warned them against being lured into the ways of the residents of the land, and against inquiring about their gods, for the residents performed for their gods every abhorrent act that God detested, even offering up their sons and daughters in fire to their gods. (Deuteronomy 12:29–31.)

Moses warned the Israelites carefully to observe only that which he enjoined upon them, neither adding to it nor taking away from it. (Deuteronomy 13:1.) If a prophet appeared before them and gave them a sign or a portent and urged them to worship another god, even if the sign or portent came true, they were not to heed the words of that prophet, but put the offender to death. (Deuteronomy 13:2–6.) If a brother, son, daughter, wife, or closest friend enticed one in secret to worship other gods, the Israelites were to show no pity, but stone the offender to death. (Deuteronomy 13:7–12.) And if they heard that some scoundrels had subverted the inhabitants of a town to worship other gods, the Israelites were to investigate thoroughly, and if they found it true, they were to destroy the inhabitants and the cattle of that town, burning the town and all its spoil as a holocaust to God. (Deuteronomy 13:13–19.) Moses prohibited the Israelites from gashing themselves or shaving the front of their heads because of the dead. (Deuteronomy 14:1.)

Kashrut[]

Moses prohibited the Israelites from eating anything abhorrent. (Deuteronomy 14:3.) Among land animals, they could eat ox, sheep, goat, deer, gazelle, roebuck, wild goat, ibex, antelope, mountain sheep, and any other animal that has true hoofs that are cleft in two and chews cud. (Deuteronomy 14:4–6.) But the Israelites were not to eat or touch the carcasses of camel, hare, daman, or swine. (Deuteronomy 14:7–8.) Of animals that live in water, they could eat anything that has fins and scales, but nothing else. (Deuteronomy 14:9–10.) They could eat any clean bird, but could not eat eagle, vulture, black vulture, kite, falcon, buzzard, raven, ostrich, nighthawk, sea gull, hawk, owl, pelican, bustard, cormorant, stork, heron, hoopoe, or bat. (Deuteronomy 14:11–18.) They could not eat any winged swarming things. (Deuteronomy 14:19.) They could not eat anything that had died a natural death, but they could give it to the stranger or you sell it to a foreigner. (Deuteronomy 14:21.) They could not boil a kid in its mother's milk. (Deuteronomy 14:21.)

Tithes[]

They were to set aside every year a tenth part of all the yield of their harvest. (Deuteronomy 14:22.) They were to consume the tithes of their new grain, wine, and oil, and the firstlings of their herds and flocks, in the presence of God in the place where God would choose to establish God's name. (Deuteronomy 14:23.) If the distance was too great to transport, they could convert the tithes or firstlings into money, take the proceeds to the place that God had chosen, and spend the money and feast there. (Deuteronomy 14:24–26.) But they were not to neglect the Levite in their community, for the Levites had no hereditary portion of land. (Deuteronomy 14:27.) Every third year, they were to bring out the full tithe, but leave it within their settlements, and the Levite, the stranger, the fatherless, and the widow in their settlements could come and eat their fill. (Deuteronomy 14:28–29.)

The Year of Jubilee (painting by Henry Le Jeune)

The Sabbatical year[]

Every seventh year, the Israelites were to remit debts from fellow Israelites, although they could continue to dun foreigners. (Deuteronomy 15:1–3.) There would be no needy among them if only they heeded God and kept all God's laws, for God would bless them. (Deuteronomy 15:4–6.) But if one of their kinsmen fell into need, they were not to harden their hearts, but were to open their hands and lend what the kinsman needed. (Deuteronomy 15:7–8.) The Israelites were not to harbor the base thought that the year of remission was approaching and not lend, but they were to lend readily to their kinsman, for in return God would bless them in all their efforts. (Deuteronomy 15:9–10.)

The Hebrew slave[]

If a fellow Hebrew was sold into servitude, the Hebrew slave would serve six years, and in the seventh year go free. (Deuteronomy 15:12.) When the master set the slave free, the master was to give the former slave parting gifts. (Deuteronomy 15:13–14.) Should the slave tell the master that the slave did not want to leave, the master was to take an awl and put it through the slave's ear into the door, and the slave was to become the master's slave in perpetuity. (Deuteronomy 15:16–17.)

The firstling[]

The Israelites were to consecrate to God all male firstlings that were born in their herds and flocks eat it with their household before God in the place that God would choose. (Deuteronomy 15:19–20.) If it had a defect, they were not to sacrifice it, but eat it in their settlements, as long as they poured out its blood on the ground. (Deuteronomy 15:21–23.)

Three pilgrim festivals[]

Moses instructed the Israelites to observe Passover, Shavuot, and Sukkot. (Deuteronomy 16:1–15.) Three times a year, on those three festivals, all Israelite men were to appear before God in the place that God would choose, each with his own gift, according to the blessing that God had bestowed upon him. (Deuteronomy 16:16–17.)

The Temple in Jerusalem

Josiah hearing the reading of Deuteronomy (illustration by Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld)

In inner-biblical interpretation[]

Deuteronomy chapter 12[]

Leviticus 17:1–10, like Deuteronomy 12:1–28, addresses the centralization of sacrifices and the permissibility of eating meat. Leviticus 17:3–4 prohibited killing an ox, lamb, or goat (each a sacrificial animal) without bringing it to the door of the Tabernacle as an offering to God. Deuteronomy 12:15, however, allows killing and eating meat in any place.

2 Kings 23:1–25 and 2 Chronicles 34:1–33 recount how King Josiah implemented the centralization called for in Deuteronomy 12:1–19.

Deuteronomy chapter 16[]

In the Hebrew Bible, Sukkot is called:

- “The Feast of Tabernacles (or Booths)” (Leviticus 23:34; Deuteronomy 16:13, 16; 31:10; Zechariah 14:16, 18, 19; Ezra 3:4; 2 Chronicles 8:13)

- “The Feast of Ingathering” (Exodus 23:16, 34:22)

- “The Feast” or “the festival” (1 Kings 8:2, 65; 12:32; 2 Chronicles 5:3; 7:8)

- “The Feast of the Lord” (Leviticus 23:39; Judges 21:19)

- “The festival of the seventh month” (Ezekiel 45:25; Nehemiah 8:14)

- “A holy convocation” or “a sacred occasion” (Numbers 29:12).

Sukkot's agricultural origin is evident from the name "The Feast of Ingathering," from the ceremonies accompanying it, and from the season and occasion of its celebration: "At the end of the year when you gather in your labors out of the field" (Exodus 23:16); "after you have gathered in from your threshing-floor and from your winepress." (Deuteronomy 16:13.) It was a thanksgiving for the fruit harvest. (Compare Judges 9:27.) And in what may explain the festival's name, Isaiah reports that grape harvesters kept booths in their vineyards. (Isaiah 1:8.) Coming as it did at the completion of the harvest, Sukkot was regarded as a general thanksgiving for the bounty of nature in the year that had passed.

Sukkot became one of the most important feasts in Judaism, as indicated by its designation as “the Feast of the Lord” (Leviticus 23:39; Judges 21:19) or simply “the Feast.” (1 Kings 8:2, 65; 12:32; 2 Chronicles 5:3; 7:8.) Perhaps because of its wide attendance, Sukkot became the appropriate time for important state ceremonies. Moses instructed the children of Israel to gather for a reading of the Law during Sukkot every seventh year. (Deuteronomy 31:10–11.) King Solomon dedicated the Temple in Jerusalem on Sukkot. (1 Kings 8; 2 Chronicles 7.) And Sukkot was the first sacred occasion observed after the resumption of sacrifices in Jerusalem after the Babylonian captivity. (Ezra 3:2–4.)

In the time of Nehemiah, after the Babylonian captivity, the Israelites celebrated Sukkot by making and dwelling in booths, a practice of which Nehemiah reports: “the Israelites had not done so from the days of Joshua.” (Nehemiah 8:13–17.) In a practice related to that of the Four Species, Nehemiah also reports that the Israelites found in the Law the commandment that they “go out to the mountains and bring leafy branches of olive trees, pine trees, myrtles, palms and [other] leafy trees to make booths.” (Nehemiah 8:14–15.) In Leviticus 23:40, God told Moses to command the people: “On the first day you shall take the product of hadar trees, branches of palm trees, boughs of leafy trees, and willows of the brook,” and “You shall live in booths seven days; all citizens in Israel shall live in booths, in order that future generations may know that I made the Israelite people live in booths when I brought them out of the land of Egypt.” (Leviticus 23:42–43.) The Book of Numbers, however, indicates that while in the wilderness, the Israelites dwelt in tents. (Numbers 11:10; 16:27.) Some secular scholars consider Leviticus 23:39–43 (the commandments regarding booths and the four species) to be an insertion by a late redactor. (E.g., Richard Elliott Friedman. The Bible with Sources Revealed, 228–29. New York: HarperSanFrancisco, 2003.)

Jeroboam son of Nebat, King of the northern Kingdom of Israel, whom 1 Kings 13:33 describes as practicing “his evil way,” celebrated a festival on the fifteenth day of the eighth month, one month after Sukkot, “in imitation of the festival in Judah.” (1 Kings 12:32–33.) “While Jeroboam was standing on the altar to present the offering, the man of God, at the command of the Lord, cried out against the altar” in disapproval. (1 Kings 13:1.)

According to Zechariah, in the messianic era, Sukkot will become a universal festival, and all nations will make pilgrimages annually to Jerusalem to celebrate the feast there. (Zechariah 14:16–19.)

In early nonrabbinic interpretation[]

Deuteronomy chapter 12[]

Josephus interpreted the centralization of worship in Deuteronomy 12:1–19 to teach that just as there is only one God, there would be only one Temple; and the Temple was to be common to all people, just as God is the God for all people. (Against Apion 2:24(193).)

A Guardian Angel (18th Century painting)

In classical rabbinic interpretation[]

Deuteronomy chapter 11[]

The Rabbis taught that the words of Deuteronomy 11:26, “Behold, I set before you this day a blessing and a curse,” demonstrate that God did not set before the Israelites the Blessings and the Curses of Leviticus 26 and Deuteronomy 28 to hurt them, but only to show them the good way that they should choose in order to receive reward. (Deuteronomy Rabbah 4:1.) Rabbi Levi compared the proposition of Deuteronomy 11:26 to a master who offered his servant a golden necklace if the servant would do the master's will, or iron chains if he did not. (Deuteronomy Rabbah 4:2.) Rabbi Haggai taught that not only had God in Deuteronomy 11:26 set two paths before the Israelites, but God did not administer justice to them according to the strict letter of the law, but allowed them mercy so that they might (in the words of Deuteronomy 30:19) “choose life.” (Deuteronomy Rabbah 4:3.) And Rabbi Joshua ben Levi taught that when a person makes the choice that Deuteronomy 11:26–27 urges and observes the words of the Torah, a procession of angels passes before the person to guard the person from evil, bringing into effect the promised blessing. (Deuteronomy Rabbah 4:4.)

Our Rabbis asked in a Baraita why Deuteronomy 11:29 says, “You shall set the blessing upon Mount Gerizim and the curse upon mount Ebal.” Deuteronomy 11:29 cannot say so merely to teach where the Israelites were to say the blessings and cursesl, as Deuteronomy 27:12–13 already says, “These shall stand upon Mount Gerizim to bless the people . . . and these shall stand upon Mount Ebal for the curse.” Rather, the Rabbis taught that the purpose of Deuteronomy 11:29 was to indicate that the blessings must precede the curses. It is possible to think that all the blessings must precede all the curses; therefore the text states “blessing” and “curse” in the singular, and thus teaches that one blessing precedes one curse, alternating blessings and curses, and all the blessings do not precede all the curses. A further purpose of Deuteronomy 11:29 is to draw a comparison between blessings and curses: As the curse was pronounced by the Levites, so the blessing had to be pronounced by the Levites. As the curse was uttered in a loud voice, so the blessing had to be uttered in a loud voice. As the curse was said in Hebrew, so the blessing had to be said in Hebrew. As the curses were in general and particular terms, so must the blessings had to be in general and particular terms. And as with the curse both parties respond “Amen,” so with the blessing both parties respond “Amen.” (Babylonian Talmud Sotah 37b.)

The Mishnah noted the common mention of the terebinths of Moreh in Deuteronomy 11:30 and Genesis 12:6 and deduced that Gerizim and Ebal were near Shechem. (Mishnah Sotah 7:5; Babylonian Talmud Sotah 32a.) But Rabbi Judah deduced from the words “beyond the Jordan” in Deuteronomy 11:30 that Gerizim and Ebal were some distance beyond the Jordan. Rabbi Judah deduced from the words “behind the way of the going down of the sun” in Deuteronomy 11:30 that Gerizim and Ebal were far from the east, where the sun rises. And Rabbi Judah also deduced from the words “over against Gilgal” in Deuteronomy 11:30 that Gerizim and Ebal were close to Gilgal. Rabbi Eleazar ben Jose said, however, that the words “Are they not beyond the Jordan” in Deuteronomy 11:30 indicated that Gerizim and Ebal were near the Jordan. (Babylonian Talmud Sotah 32b.)

Deuteronomy chapter 12[]

Rabbi Jose son of Rabbi Judah derived from the use of the two instances of the verb “destroy” in the Hebrew for “you shall surely destroy” in Deuteronomy 12:2 that the Israelites were to destroy the Canaanite's idols twice, and the Rabbis explained that this meant by cutting them and then by uprooting them from the ground. The Gemara explained that Rabbi Jose derived from the words “and you shall destroy their name out of that place” in Deuteronomy 12:3 that the place of the idol must be renamed. And Rabbi Eliezer deduced from the same words in Deuteronomy 12:3 that the Israelites were to eradicate every trace of the idol. (Babylonian Talmud Avodah Zarah 45b.)

Plan of the Tabernacle, Solomon's Temple, and Herod's Temple

The Mishnah recounted the history of decentralized sacrifice. Before the Tabernacle, high places were permitted, and Israelite firstborn performed the sacrifices. After the Israelites set up the Tabernacle, high places were forbidden, and priests performed the services. When the Israelites entered the Promised Land and came to Gilgal, high places were again permitted. When the Israelites came to Shiloh, high places were again forbidden. The Tabernacle there had no roof, but consisted of a stone structure covered with cloth. The Mishnah interpreted the Tabernacle at Shiloh to be the “rest” to which Moses referred in Deuteronomy 12:9. When the Israelites came to Nob and Gibeon, high places were again permitted. And when the Israelites came to Jerusalem, high places were forbidden and never again permitted. The Mishnah interpreted the sanctuary in Jerusalem to be “the inheritance” to which Moses referred in Deuteronomy 12:9. (Mishnah Zevachim 14:4–8; Babylonian Talmud Zevachim 112b.) The Mishnah explained the different practices at the various high places when high places were permitted. The Mishnah taught that there was no difference between a Great Altar (at the Tabernacle or the Temple) and a small altar (a local high place), except that the Israelites had to bring obligatory sacrifices that had a fixed time, like the Passover sacrifice, to the Great Altar. (Mishnah Megillah 1:10; Babylonian Talmud Megillah 9b.) Further, the Mishnah explained that there was no difference between Shiloh and Jerusalem except that in Shiloh they ate minor sacrifices and second tithes (ma'aser sheni) anywhere within sight of Shiloh, whereas at Jerusalem they were eaten within the wall. And the sanctity of Shiloh was followed by a period when high places were permitted, while after the sanctity of Jerusalem high places were no longer permitted. (Mishnah Megillah 1:11; Babylonian Talmud Megillah 9b–10a.)

King Solomon and the Plan for the Temple (illustration from a Bible card published 1896 by the Providence Lithograph Company)

Rabbi Judah (or some say Rabbi Jose) said that three commandments were given to the Israelites when they entered the land: (1) the commandment of Deuteronomy 17:14–15 to appoint a king, (2) the commandment of Deuteronomy 25:19 to blot out Amalek, and (3) the commandment of Deuteronomy 12:10–11 to build the Temple in Jerusalem. Rabbi Nehorai, on the other hand, said that Deuteronomy 17:14–15 did not command the Israelites to choose a king, but was spoken only in anticipation of the Israelites’ future complaints, as Deuteronomy 17:14 says, “And (you) shall say, ‘I will set a king over me.’” A Baraita taught that because Deuteronomy 12:10–11 says, “And when He gives you rest from all your enemies round about,” and then proceeds, “then it shall come to pass that the place that the Lord your God shall choose,” it implies that the commandment to exterminate Amalek was to come before building of the Temple. (Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 20b.)

Tractate Chullin in the Mishnah, Tosefta, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of the slaughter of animals for purposes other than sacrifice in Deuteronomy 12:15–25. (Mishnah Chullin 1:1–12:5; Tosefta Shechitat Chullin 1:1–10:16; Babylonian Talmud Chullin 2a–142a.)

Tractate Bikkurim in the Mishnah, Tosefta, and Jerusalem Talmud interpreted the laws of the first fruits in Exodus 23:19, Numbers 18:13, and Deuteronomy 12:17–18 and 26:1–11. (Mishnah Bikkurim 1:1–3:12; Tosefta Bikkurim 1:1–2:16; Jerusalem Talmud Bikkurim 1a–26b.)

Deuteronomy chapter 13[]

The Jerusalem Talmud interpreted Deuteronomy 13:2 — “a prophet . . . gives you a sign or a wonder” — to demonstrate that a prophet's authority depends on the prophet's producing a sign or wonder. (Jerusalem Talmud Berakhot 12a.)

Mishnah Sanhedrin 10:4–6, Tosefta Sanhedrin 14:1–6, and Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 111b–13b interpreted Deuteronomy 13:13–19 to address the law of the apostate town. The Mishnah held that only a court of 71 judges could declare such a city, and the court could not declare cities on the frontier or three cities within one locale to be apostate cities. (Mishnah Sanhedrin 1:5; Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 2a.) A Baraita taught that there never was an apostate town and never will be. Rabbi Eliezer said that no city containing even a single mezuzah could be condemned as an apostate town, as Deuteronomy 13:17 instructs with regard to such a town, “you shall gather all the spoil of it in the midst of the street thereof and shall burn . . . all the spoil,” but if the spoil contains even a single mezuzah, this burning would be forbidden by the injunction of Deuteronomy 12:3–4, which states, “you shall destroy the names of [the idols] . . . . You shall not do so to the Lord your God,” and thus forbids destroying the Name of God. Rabbi Jonathan, however, said that he saw an apostate town and sat upon its ruins. (Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 71a.)

Deuteronomy chapter 14[]

Tractates Maasrot and Maaser Sheni in the Mishnah, Tosefta, and Jerusalem Talmud interpreted the laws of tithes in Leviticus 27:30–33, Numbers 18:21–24, and Deuteronomy 14:22–29. (Mishnah Maasrot 1:1–5:8; Tosefta Maasrot 1:1–3:16; Jerusalem Talmud Maasrot 1a–46a; Mishnah Maaser Sheni 1:1–5:15; Tosefta Maaser Sheni 1:1–5:30; Jerusalem Talmud Maaser Sheni 1a–59b.)

The precept of Deuteronomy 14:26 to rejoice on the festivals (or some say the precept of Deuteronomy 16:14 to rejoice on the festival of Sukkot) is incumbent upon women notwithstanding the general rule that the law does not bind women to observe precepts that depend on a certain time. (Babylonian Talmud Eruvin 27a.)

Mishnah Peah 8:5–9 and Tosefta Peah 4:2–10 interpreted Deuteronomy 14:28–29 to address the tithe given to the poor and the Levite.

A Baraita deduced from the parallel use of the words “at the end” in Deuteronomy 14:28 (regarding tithes) and 31:10 (regarding the great assembly) that just as the Torah required the great assembly to be done at a festival (Deuteronomy 31:10), the Torah also required tithes to be removed at the time of a festival. (Jerusalem Talmud Maaser Sheni 53a.)

Deuteronomy chapter 15[]

Tractate Sheviit in the Mishnah, Tosefta, and Jerusalem Talmud interpreted the laws of the Sabbatical year in Exodus 23:10–11, Leviticus 25:1–34, and Deuteronomy 15:1–18, and 31:10–13. (Mishnah Sheviit 1:1–10:9; Tosefta Sheviit 1:1–8:11; Jerusalem Talmud Sheviit 1a–87b.)

Hillel (sculpture at the Knesset Menorah, Jerusalem)

Mishnah Sheviit chapter 10 and Tosefta Sheviit 8:3–11 interpreted Deuteronomy 15:1–10 to address debts and the Sabbatical year. The Mishnah held that the Sabbatical year cancelled loans, whether they were secured by a bond or not, but did not cancel debts to a shopkeeper or unpaid wages of a laborer, unless these debts were made into loans. (Mishnah Sheviit 10:1.) When Hillel saw people refraining from lending, in transgression of Deuteronomy 15:9, he ordained the prosbul, which ensured the repayment of loans notwithstanding the Sabbatical year. (Mishnah Sheviit 10:3.) Citing the literall meaning of Deuteronomy 15:2 — “this is the word of the release” — the Mishnah held that a creditor could accept payment of a debt notwithstanding an intervening Sabbatical year, if the creditor had first by word told the debtor that the creditor relinquished the debt. (Mishnah Sheviit 10:8.)

Rabbi Isaac taught that the words of Psalm 103:20, “mighty in strength that fulfill His word,” speak of those who observe the Sabbatical year. Rabbi Isaac said that we often find that a person fulfills a precept for a day, a week, or a month, but it is remarkable to find one who does so for an entire year. Rabbi Isaac asked whether one could find a mightier person than one who sees his field untilled, see his vineyard untilled, and yet pays his taxes and does not complain. And Rabbi Isaac noted that Psalm 103:20 uses the words “that fulfill His word (dabar),” and Deuteronomy 15:2 says regarding observance of the Sabbatical year, “And this is the manner (dabar) of the release,” and argued that “dabar” means the observance of the Sabbatical year in both places. (Leviticus Rabbah 1:1.)

Rabbi Shila of Nawha (a place east of Gadara in the Galilee) interpreted the word “needy” (אֶבְיוֹן, evyon) in Deuteronomy 15:7 to teach that one should give to the poor person from one's wealth, for that wealth is the poor person's, given to you in trust. Rabbi Abin observed that when a poor person stands at one's door, God stands at the person's right, as Psalm 109:31 says: “Because He stands at the right hand of the needy.” If one gives something to a poor person, one should reflect that the One who stands at the poor person's right will reward the giver. And if one does not give anything to a poor person, one should reflect that the One who stands at the poor person's right will punish the one who did not give, as Psalm 109:31 says: “He stands at the right hand of the needy, to save him from them that judge his soul.” (Leviticus Rabbah 34:9.)

Charity (illustration from a Bible card published 1897 by the Providence Lithograph Company)

The Rabbis interpreted the words “sufficient for his need, whatever is lacking for him” in Deuteronomy 15:8 to teach the level to which the community must help an impoverished person. Based on these words, the Rabbis taught in a Baraita that if an orphan applied to the community for assistance to marry, the community must rent a house, supply a bed and necessary household furnishings, and put on the wedding, as Deuteronomy 15:8 says, “sufficient for his need, whatever is lacking for him.” The Rabbis interpreted the words “sufficient for his need” to refer to the house, “whatever is lacking” to refer to a bed and a table, and “for him (לוֹ, lo)” to refer to a wife, as Genesis 2:18 uses the same term, “for him (לוֹ, lo),” to refer to Adam’s wife, whom Genesis 2:18 calls “a helpmate for him.” The Rabbis taught that the words “sufficient for his need” command us to maintain the poor person, but not to make the poor person rich. But the Gemara interpreted the words “whatever is lacking for him” to include even a horse to ride upon and a servant to run before the impoverished person, if that was what the particular person lacked. The Gemara told that once Hillel bought for a certain impoverished man from an affluent family a horse to ride upon and a servant to run before him, and once when Hillel could not find a servant to run before the impoverished man, Hillel himself ran before him for three miles. The Rabbis taught in a Baraita that once the people of Upper Galilee bought a pound of meat every day for an impoverished member of an affluent family of Sepphoris. Rav Huna taught that they bought for him a pound of premium poultry, or if you prefer, the amount of ordinary meat that they could buy with a pound of money. Rav Ashi taught that the place was such a small village with so few buyers for meat that every day they had to waste a whole animal just to provide for the pauper's needs. Once when a pauper applied to Rabbi Nehemiah for support, Rabbi Nehemiah asked him of what his meals consisted. The pauper told Rabbi Nehemiah that he had been used to eating well-marbled meat and aged wine. Rabbi Nehemiah asked him whether he could get by with Rabbi Nehemiah on a diet of lentils. The pauper consented, joined Rabbi Nehemiah on a diet of lentils, and then died. Rabbi Nehemiah lamented that he had caused the pauper's death by not feeding him the diet to which he had been accustomed, but the Gemara answered that the pauper himself was responsible for his own death, for he should not have allowed himself to become dependent on such a luxurious diet. Once when a pauper applied to Rava for support, Rava asked him of what his meals consisted. The pauper told Rava that he had been used to eating fattened chicken and aged wine. Rava asked the pauper whether he considered the burden on the community of maintaining such a lifestyle. The pauper replied that he was not eating what the community provided, but what God provided, as Psalm 145:15 says: “The eyes of all wait for You, and You give them their food in due season.” As the verse does not say “in their season” (in the plural), but “in His season” (in the singular), it teaches that God provides every person the food that the person needs. Just then, Rava's sister, who had not seen him for 13 years, arrived with a fattened chicken and aged wine. Thereupon, Rava exclaimed at the coincidence, apologized to the pauper, and invited him to come and eat. (Babylonian Talmud Ketubot 67b.)

The Gemara turned to how the community should convey assistance to the pauper. Rabbi Meir taught that if a person has no means but does not wish to receive support from the community's charity fund, then the community should give the person what the person requires as a loan and then convert the loan into a gift by not collecting repayment. The Sages, however, said (as Rava explained their position) that the community should offer the pauper assistance as a gift, and then if the pauper declines the gift, the community should extend funds to the pauper as a loan. The Gemara taught that if a person has the means for self-support but chooses rather to rely on the community, then the community may give the person what the person needs as a gift, and then make the person repay it. As requiring repayment would surely cause the person to decline assistance on a second occasion, Rav Papa explained that the community exacts repayment from the person's estate upon the person's death. Rabbi Simeon taught that the community need not become involved if a person who has the means for self-support chooses not to do so. Rabbi Simeon taught that if a person has no means but does not wish to receive support from the community's charity fund, then the community should ask for a pledge in exchange for a loan, so as thereby to raise the person's self-esteem. The Rabbis taught in a Baraita that the instruction to “lend” in Deuteronomy 15:8 refers to the person who has no means and is unwilling to receive assistance from the community's charity fund, and to whom the community must thus offer assistance as a loan and then give it as a gift. Rabbi Judah taught that the words “you . . . shall surely lend him” in Deuteronomy 15:8 refer to the person who has the means for self-support but chooses rather to rely on the community, to whom the community should give what the person needs as a gift, and then exact repayment from the person's estate upon the person's death. The Sages, however, said that the community has no obligation to help the person who has the means of self-support. According to the Sages, the use of the emphatic words “you . . . shall surely lend him” in Deuteronomy 15:8 (in which the Hebrew verb for “lend” is doubled, וְהַעֲבֵט, תַּעֲבִיטֶנּוּ) is merely stylistic and without legal significance. (Babylonian Talmud Ketubot 67b.)

Judah and Tamar (painting by the school of Rembrandt)

The Gemara related a story about how to give to the poor. A poor man lived in Mar Ukba's neighborhood, and every day Mar Ukba would put four zuz into the poor man's door socket. One day, the poor man thought that he would try to find out who did him this kindness. That day Mar Ukba came home from the house of study with his wife. When the poor man saw them moving the door to make their donation, the poor man went to greet them, but they fled and ran into a furnace from which the fire had just been swept. They did so because, as Mar Zutra bar Tobiah said in the name of Rav (or others say Rav Huna bar Bizna said in the name of Rabbi Simeon the Pious, and still others say Rabbi Johanan said in the name of Rabbi Simeon ben Yohai), it is better for a person to go into a fiery furnace than to shame a neighbor publicly. One can derive this from Genesis 38:25, where Tamar, who was subject to being burned for the adultery with which Judah had charged her, rather than publicly shame Judah with the facts of his complicity, sent Judah's possessions to him with the message, “By the man whose these are am I with child.” (Babylonian Talmud Ketubot 67b.)

The Gemara related another story of Mar Ukba's charity. A poor man lived in Mar Ukba's neighborhood to whom he regularly sent 400 zuz on the eve of every Yom Kippur. Once Mar Ukba sent his son to deliver the 400 zuz. His son came back and reported that the poor man did not need Mar Ukba's help. When Mar Ukba asked his son what he had seen, his son replied that they were sprinkling aged wine before the poor man to improve the aroma in the room. Mar Ukba said that if the poor man was that delicate, then Mar Ukba would double the amount of his gift and send it back to the poor man. (Babylonian Talmud Ketubot 67b.)

When Mar Ukba was about to die, he asked to see his charity accounts. Finding gifts worth 7,000 Sijan gold denarii recorded therein, he exclaimed that the provisions were scanty and the road was long, and he forthwith distributed half of his wealth to charity. The Gemara asked how Mar Ukba could have given away so much, when Rabbi Elai taught that when the Sanhedrin sat at Usha, it ordained that if a person wishes to give liberally the person should not give more than a filth of the person's wealth. The Gemara explained that this limitation applies only during a person's lifetime, as the person might thereby be impoverished, but the limitation does not apply to gifts at death. (Babylonian Talmud Ketubot 67b.)

The Gemara related another story about a Sage's charity. Rabbi Abba used to bind money in his scarf, sling it on his back, and go among the poor so that they could take the funds they needed from his scarf. He would, however, look sideways as a precaution against swindlers. (Babylonian Talmud Ketubot 67b.)

Rabbi Hiyya bar Rav of Difti taught that Rabbi Joshua ben Korha deduced from the parallel use of the term “base” with regard to withholding charity and practicing idolatry that people who shut their eyes against charity are like those who worship idols. Deuteronomy 15:9 says regarding aid to the poor, “Beware that there be not a base thought in your heart . . . and your eye will be evil against your poor brother,” while Deuteronomy 13:14 uses the same term “base” when it says regarding idolatry, “Certain base fellows are gone out from the midst of you . . . saying: ‘Let us go and serve other gods there.’” That Deuteronomy employs the same adjective for both failings implies that withholding charity and practicing idolatry are similar. (Babylonian Talmud Ketubot 68a.)

Deuteronomy chapter 16[]

Tractate Pesachim in the Mishnah, Tosefta, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of the Passover in Exodus 12:3–27, 43–49; 13:6–10; 34:25; Leviticus 23:4–8; Numbers 9:1–14; and Deuteronomy 16:1–8. (Mishnah Pesachim 1:1–10:9; Tosefta Pisha 1:1–10:13; Jerusalem Talmud Pesachim 1a–; Babylonian Talmud Pesachim 2a–121b.)

Tractate Beitzah in the Mishnah, Tosefta, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws common to all of the Festivals in Exodus 12:3–27, 43–49; 13:6–10; 23:16; 34:18–23; Leviticus 16; 23:4–43; Numbers 9:1–14; 28:16–30:1; and Deuteronomy 16:1–17; 31:10–13. (Mishnah Beitzah 1:1–5:7; Tosefta Yom Tov (Beitzah) 1:1–4:11; Jerusalem Talmud Beitzah 1a–; Babylonian Talmud Beitzah 2a–40b.)

Rabbi Elazar ben Azariah argued that Jews must mention the Exodus every night, but did not prevail in his argument until Ben Zoma argued that Deuteronomy 16:3, which commands a Jew to remember the Exodus “all the days of your life,” used the word “all” to mean both day and night. (Mishnah Berakhot 1:5; Babylonian Talmud Berakhot 12b.)

The Mishnah reported that Jews read Deuteronomy 16:9–12 on Shavuot. (Mishnah Megillah 3:5; Babylonian Talmud Megillah 30b.) So as to maintain a logical unit including at least 15 verses, Jews now read Deuteronomy 15:19–16:17 on Shavuot.

Tractate Sukkah in the Mishnah, Tosefta, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of Sukkot in Exodus 23:16; 34:22; Leviticus 23:33–43; Numbers 29:12–34; and Deuteronomy 16:13–17; 31:10–13. (Mishnah Sukkah 1:1–5:8; Tosefta Sukkah 1:1–4:28; Jerusalem Talmud Sukkah 1a–33b; Babylonian Talmud Sukkah 2a–56b.)

Eating in a Sukkah (1723 engraving by Bernard Picart)

The Mishnah taught that a sukkah can be no more than 20 cubits high. Rabbi Judah, however, declared taller sukkot valid. The Mishnah taught that a sukkah must be at least 10 handbreadths high, have three walls, and have more shade than sun. (Mishnah Sukkah 1:1; Babylonian Talmud Sukkah 2a.) The House of Shammai declared invalid a sukkah made 30 days or more before the festival, but the House of Hillel pronounced it valid. The Mishnah taught that if one made the sukkah for the purpose of the festival, even at the beginning of the year, it is valid. (Mishnah Sukkah 1:1; Babylonian Talmud Sukkah 9a.)

The Mishnah taught that a sukkah under a tree is as invalid as a sukkah within a house. If one sukkah is erected above another, the upper one is valid, but the lower is invalid. Rabbi Judah said that if there are no occupants in the upper one, then the lower one is valid. (Mishnah Sukkah 1:2 ; Babylonian Talmud Sukkah 9b.)

It invalidates a sukkah to spread a sheet over the sukkah because of the sun, or beneath it because of falling leaves, or over the frame of a four-post bed. One may spread a sheet, however, over the frame of a two-post bed. (Mishnah Sukkah 1:3; Babylonian Talmud Sukkah 10a.)

It is not valid to train a vine, gourd, or ivy to cover a sukkah and then cover it with sukkah covering (s’chach). If, however, the sukkah-covering exceeds the vine, gourd, or ivy in quantity, or if the vine, gourd, or ivy is detached, it is valid. The general rule is that one may not use for sukkah-covering anything that is susceptible to ritual impurity (tumah) or that does not grow from the soil. But one may use for sukkah-covering anything not susceptible to ritual impurity that grows from the soil. (Mishnah Sukkah 1:4; Babylonian Talmud Sukkah 11a.)

Bundles of straw, wood, or brushwood may not serve as sukkah-covering. But any of them, if they are untied, are valid. All materials are valid for the walls. (Mishnah Sukkah 1:5; Babylonian Talmud Sukkah 12a.)

Rabbi Judah taught that one may use planks for the sukkah-covering, but Rabbi Meir taught that one may not. The Mishnah taught that it is valid to place a plank four handbreadths wide over the sukkah, provided that one does not sleep under it. (Mishnah Sukkah 1:6; Babylonian Talmud Sukkah 14a.)

The Gemara deduced from the parallel use of the word “appear” in Exodus 23:14 and Deuteronomy 16:15 (regarding appearance offerings) on the one hand, and in Deuteronomy 31:10–12 (regarding the great assembly) on the other hand, that the criteria for who participated in the great assembly also applied to limit who needed to bring appearance offerings. A Baraita deduced from the words “that they may hear” in Deuteronomy 31:12 that a deaf person was not required to appear at the assembly. And the Baraita deduced from the words “that they may learn” in Deuteronomy 31:12 that a mute person was not required to appear at the assembly. But the Gemara questioned the conclusion that one who cannot talk cannot learn, recounting the story of two mute grandsons (or others say nephews) of Rabbi Johanan ben Gudgada who lived in Rabbi’s neighborhood. Rabbi prayed for them, and they were healed. And it turned out that notwithstanding their speech impediment, they had learned halachah, Sifra, Sifre, and the whole Talmud. Mar Zutra and Rav Ashi read the words “that they may learn” in Deuteronomy 31:12 to mean “that they may teach,” and thus to exclude people who could not speak from the obligation to appear at the assembly. Rabbi Tanhum deduced from the words “in their ears” (using the plural for “ears”) at the end of Deuteronomy 31:11 that one who was deaf in one ear was exempt from appearing at the assembly. (Babylonian Talmud Chagigah 3a.)

Mishnah Chagigah 1:1–8 and Tosefta Chagigah 1:1–7 interpreted Deuteronomy 16:16–17 to address the obligation to bring an offering on the three pilgrim festivals.

Commandments[]

According to Sefer ha-Chinuch, there are 17 positive and 38 negative commandments in the parshah.

- To destroy idols and their accessories (Deuteronomy 12:2.)

- Not to destroy objects associated with God's Name (Deuteronomy 12:4.)

- To bring all avowed and freewill offerings to the Temple on the first subsequent festival (Deuteronomy 12:5-6.)

- Not to offer any sacrifices outside the Temple courtyard (Deuteronomy 12:13.)

- To offer all sacrifices in the Temple (Deuteronomy 12:14.)

- To redeem dedicated animals which have become disqualified (Deuteronomy 12:15.)

- Not to eat the second tithe of grains outside Jerusalem (Deuteronomy 12:17.)

- Not to eat the second tithe of wine products outside Jerusalem (Deuteronomy 12:17.)

- Not to eat the second tithe of oil outside Jerusalem (Deuteronomy 12:17.)

- The Kohanim must not eat unblemished firstborn animals outside Jerusalem (Deuteronomy 12:17.)

- The Kohanim must not eat sacrificial meat outside the Temple courtyard (Deuteronomy 12:17.)

- Not to eat the meat of the burnt offering (Deuteronomy 12:17.)

- Not to eat the meat of minor sacrifices before sprinkling the blood on the altar (Deuteronomy 12:17.)

- The Kohanim must not eat first fruits before they are set down in the Sanctuary grounds (Deuteronomy 12:17.)

- Not to refrain from rejoicing with, and giving gifts to, the Levites (Deuteronomy 12:19.)

- To ritually slaughter an animal before eating it (Deuteronomy 12:21.)

- Not to eat a limb or part taken from a living animal (Deuteronomy 12:23.)

- To bring all sacrifices from outside Israel to the Temple (Deuteronomy 12:26.)

- Not to add to the Torah commandments or their oral explanations (Deuteronomy 13:1.)

- Not to diminish from the Torah any commandments, in whole or in part (Deuteronomy 13:1.)

- Not to listen to a false prophet (Deuteronomy 13:4.)

- Not to love an enticer to idolatry (Deuteronomy 13:9.)

- Not to cease hating the enticer to idolatry (Deuteronomy 13:9.)

- Not to save the enticer to idolatry (Deuteronomy 13:9.)

- Not to say anything in defense of the enticer to idolatry (Deuteronomy 13:9.)

- Not to refrain from incriminating the enticer to idolatry (Deuteronomy 13:9.)

- Not to entice an individual to idol worship (Deuteronomy 13:12.)

- Carefully interrogate the witness (Deuteronomy 13:15.)

- To burn a city that has turned to idol worship (Deuteronomy 13:17.)

- Not to rebuild it as a city (Deuteronomy 13:17.)

- Not to derive benefit from it (Deuteronomy 13:18.)

- Not to tear the skin in mourning (Deuteronomy 14:1.)

- Not to make a bald spot in mourning (Deuteronomy 14:1.)

- Not to eat sacrifices which have become unfit or blemished (Deuteronomy 14:3.).

- To examine the signs of fowl to distinguish between kosher and non-kosher (Deuteronomy 14:11.)

- Not to eat non-kosher flying insects (Deuteronomy 14:19.)

- Not to eat the meat of an animal that died without ritual slaughter (Deuteronomy 14:21.)

- To set aside the second tithe (Ma'aser Sheni) (Deuteronomy 14:22.)

- To separate the tithe for the poor (Deuteronomy 14:28.)

- Not to pressure or claim from the borrower after the seventh year (Deuteronomy 15:2.)

- To press the idolater for payment (Deuteronomy 15:3.)

- To release all loans during the seventh year (Deuteronomy 15:2.)

- Not to withhold charity from the poor (Deuteronomy 15:7.)

- To give charity (Deuteronomy 15:8.)

- Not to refrain from lending immediately before the release of the loans for fear of monetary loss (Deuteronomy 15:9.)

- Not to send the Hebrew slave away empty-handed (Deuteronomy 15:13.)

- Give the Hebrew slave gifts when he goes free (Deuteronomy 15:14.)

- Not to work consecrated animals (Deuteronomy 15:19.)

- Not to shear the fleece of consecrated animals (Deuteronomy 15:19.)

- Not to eat chametz on the afternoon of the 14th day of Nisan (Deuteronomy 16:3.)

- Not to leave the meat of the holiday offering of the 14th until the 16th (Deuteronomy 16:4.)

- Not to offer a Passover offering on one's provisional altar (Deuteronomy 16:5.)

- To rejoice on these three Festivals (Deuteronomy 16:14.)

- To be seen at the Temple on Passover, Shavuot, and Sukkot (Deuteronomy 16:16.)

- Not to appear at the Temple without offerings (Deuteronomy 16:16.)

Isaiah (fresco by Michelangelo)

(Sefer HaHinnuch: The Book of [Mitzvah] Education. Translated by Charles Wengrov, 4:357–511. Jerusalem: Feldheim Pub., 1988. ISBN 0-87306-457-7.)

Haftarah[]

The haftarah for the parshah is Isaiah 54:11–55:5. The haftarah is the third in the cycle of seven haftarot of consolation after Tisha B'Av, leading up to Rosh Hashanah.

In some congregations, when Re'eh falls on 29 Av, and thus coincides with Shabbat Machar Chodesh (as it did in 2008), the haftarah is 1 Samuel 20:18–42. In other congregations, when Re'eh coincides with Shabbat Machar Chodesh, the haftarah is not changed to 1 Samuel 20:18–42 (the usual haftarah for Shabbat Machar Chodesh), but is kept as it would be in a regular year at Isaiah 54:11–55:5.

When Re'eh falls on 30 Av and thus coincides with Shabbat Rosh Chodesh (as it does in 2012, 2015, and 2016), the haftarah is changed to Isaiah 66:1-23. In those years, the regular haftarah for Re'eh (Isaiah 54:11–55:5) is pushed off two weeks later, to Parshat Ki Teitzei (which in those years falls on 14 Elul), as the haftarot for Re'eh and Ki Teitzei are positioned next to each other in Isaiah.

A page from the Kaufmann Haggadah

In the liturgy[]

In the Passover Haggadah (which takes the story from Mishnah Berakhot 1:5), Rabbi Eleazar ben Azariah discusses Ben Zoma's exposition on Deuteronomy 16:3 in the discussion among the Rabbis at Bnei Brak in the answer to the Four Questions (Ma Nishtana) in the magid section of the Seder. (Menachem Davis. The Interlinear Haggadah: The Passover Haggadah, with an Interlinear Translation, Instructions and Comments, 37. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2005. ISBN 1-57819-064-9. Joseph Tabory. JPS Commentary on the Haggadah: Historical Introduction, Translation, and Commentary, 85. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 2008. ISBN 978-0-8276-0858-0.)

Further reading[]

The parshah has parallels or is discussed in these sources:

Biblical[]

- Genesis 14:20 (tithe); 28:22 (tithe).

- Exodus 12:3–27, 43–49 (Passover); 13:6–10 (Passover); 21:1–11, 20–21, 26–27; 22:1–2; 23:14–19 (three pilgrim festivals); 34:22–26 (three pilgrim festivals).

- Leviticus 17:1–10 (centralization of sacrifices); 23:4–43 (three pilgrim festivals); 25:8–10, 39–55; 27:30–33 (tithes).

- Numbers 9:1–14 (Passover); 18:21-24 (tithes); 28:16–31 (Passover, Shavuot); 29:12–34 (Sukkot).

- Deuteronomy 20:10–14; 21:10–14; 23:16–17; 26:13–14; 30:19 (I set before you blessing and curse); 31:10–13 (Sukkot).

- Judges 21:19 (Sukkot).

- 1 Samuel 8:15–17 (tithes).

- 1 Kings 8:1–66 (Sukkot); 12:32 (northern feast like Sukkot); 18:28 (ceremonial cutting).

- 2 Kings 4:1–7 (debt servitude); 23:1–25 (centralization of sacrifices).

- Isaiah 61:1–2 (liberty to captives).

- Jeremiah 16:6; 34:6–27; 41:5 (ceremonial cutting); 48:37 (ceremonial cutting).

- Ezekiel 6:13 (idols on hill, on mountains, under every leafy tree); 45:25 (Sukkot).

- Hosea 4:13 (idols on mountains, on hill, under tree).

- Amos 2:6; 4:4–5 (tithes).

- Zechariah 14:16–19 (Sukkot).

- Malachi 3:10 (tithes).

- Ezra 3:4 (Sukkot).

- Nehemiah 5:1–13; 8:14–18 (Sukkot); 10:38–39 (tithes); 12:44, 47 (tithes); 13:5, 12–13 (tithes).

- 2 Chronicles 5:3–14 (Sukkot); 7:8 (Sukkot); 8:12–13 (three Pilgrim festivals); 31:4–12 (tithes); 34:1–33 (centralization of sacrifices).

Josephus

Early nonrabbinic[]

- 1 Maccabees 3:49; 10:31; 11:35. Land of Israel, circa 100 B.C.E. (tithes).

- Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 4:8:2–5, 7–8, 13, 28, 44–45. Circa 93–94. Against Apion 2:24(193). Circa 97. Reprinted in, e.g., The Works of Josephus: Complete and Unabridged, New Updated Edition. Translated by William Whiston, 114–17, 121, 123–24, 806. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson Pub., 1987. ISBN 0-913573-86-8.

- Hebrews 7:1–10 (tithes).

- Matthew 23:23–24 (tithes).

- Luke 18:9–14 (tithes).

- John 7:1-53 (Sukkot).

Classical rabbinic[]

- Mishnah: Berakhot 1:5; Peah 8:5–9; Sheviit 1:1–10:9; Terumot 3:7; Maasrot 1:1–5:8; Maaser Sheni 1:1–5:15; Challah 1:3; Bikkurim 1:1–3:12; Shabbat 9:6; Pesachim 1:1–10:9; Sukkah 1:1–5:8; Beitzah 1:1–5:7; Megillah 1:3, 3:5; Chagigah 1:1–8; Ketubot 5:6; Sotah 7:5, 8; Kiddushin 1:2–3; Sanhedrin 1:3, 5, 10:4–6; Makkot 3:5, 15; Avodah Zarah 3:3–4; Avot 3:14; Zevachim 9:5, 14:2, 6; Menachot 7:6–8:1; Chullin 1:1–12:5; Bekhorot 4:1; Arakhin 8:7. Land of Israel, circa 200 C.E. Reprinted in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988. ISBN 0-300-05022-4.

- Tosefta: Berakhot 1:10; Peah 1:1, 4:2–10, 17, 20; Kilayim 1:9; Sheviit 1:1–8:11; Maasrot 1:1–3:16; Maaser Sheni 1:1–5:30; Bikkurim 1:1–2:16; Pisha 1:1–10:13; Sukkah 1:1–4:28; Yom Tov (Beitzah) 1:1–4:11; Megillah 3:5; Chagigah 1:1, 4–8; Ketubot 6:8; Sotah 7:17, 8:7, 10:2, 14:7; Bava Kamma 9:30; Sanhedrin 3:5–6, 7:2, 14:1–6; Makkot 5:8–9; Shevuot 3:8; Avodah Zarah 3:19, 6:10; Horayot 2:9; Zevachim 4:2, 13:16, 20; Shechitat Chullin 1:1–10:16; Menachot 9:2; Bekhorot 1:9, 7:1; Arakhin 4:26. Land of Israel, circa 300 C.E. Reprinted in, e.g., The Tosefta: Translated from the Hebrew, with a New Introduction. Translated by Jacob Neusner. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson Pub., 2002. ISBN 1-56563-642-2.

- Sifre to Deuteronomy 53:1–143:5. Land of Israel, circa 250–350 C.E. Reprinted in, e.g., Sifre to Deuteronomy: An Analytical Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, 1:175–342. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1987. ISBN 1-55540-145-7.

- Jerusalem Talmud: Berakhot 12a, 16b, 27a, 32b; Peah 15b, 42b, 72a; Sheviit 1a–87b; Maasrot 1a–46a; Maaser Sheni 1a–59b; Challah 9b, 10b, 11a; Orlah 8a, 35a; Bikkurim 1a–26b; Pesachim 1a–; Sukkah 1a–33b; Beitzah 1a–. Land of Israel, circa 400 C.E. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Yerushalmi. Edited by Chaim Malinowitz, Yisroel Simcha Schorr, and Mordechai Marcus, vols. 1–3, 6a–b, 9–12, 22. Brooklyn: Mesorah Pubs., 2005–2009.

Talmud

- Babylonian Talmud: Berakhot 9a, 12b, 21a, 31b, 34b, 39b, 45a, 47b; Shabbat 22b, 31a, 54a, 63a, 90a, 94b, 108a, 119a, 120b, 128a, 130a, 148b, 151b; Eruvin 27a–28a, 31b, 37a, 80b, 96a, 100a; Pesachim 2a–121b; Yoma 2b, 34b, 36b, 56a, 70b, 75b–76a; Sukkah 2a–56b; Beitzah 2a–40b; Rosh Hashanah 4b–7a, 8a, 12b–13a, 14a, 21a, 28a; Taanit 9a, 21a; Megillah 5a, 9b–10a, 16b, 30b–31a; Moed Katan 2b–3a, 7b–8b, 12a, 13a, 14b, 15b, 18b–19a, 20a, 24b; Chagigah 2a–b, 3b, 4b, 5b–6b, 7b–9a, 10b, 16b–18a; Yevamot 9a, 13b, 62b, 73a–b, 74b, 79a, 83b, 86a, 93a, 104a; Ketubot 43a, 55a, 58b, 60a, 67b–68a, 89a; Nedarim 13a, 19a, 31a, 36b, 59b; Nazir 4b, 25a, 35b, 49b–50a; Sotah 14a, 23b, 32a–b, 33b, 38a, 39b, 41a, 47b–48a; Gittin 18a, 25a, 30a, 31a, 36a, 37a–b, 38b, 47a, 65a; Kiddushin 11b, 14b–15a, 16b–17b, 20a, 21b–22b, 26a, 29b, 34a–b, 35b–36a, 37a, 38b, 56b–57b, 80b; Bava Kamma 7a, 10a, 41a, 54a–b, 63a, 69b, 78a, 82b, 87b, 91b, 98a, 106b, 110b, 115b; Bava Metzia 6b, 27b, 30b, 31b, 33a, 42a, 44b–45a, 47b, 48b, 53b–54a, 56a, 88b, 90a; Bava Batra 8a, 10a, 63a, 80b, 91a, 145b; Sanhedrin 2a, 4a–b, 11b, 13b, 15b, 20b, 21b, 29a, 30b, 32a, 33b, 34b, 36b, 40a–41a, 43a, 45b, 47a–b, 50a, 52b, 54b, 55a, 56a, 59a, 60b, 61a–b, 63a–b, 64b, 70a, 71a, 78a, 84a, 85b, 87a, 89b–90a, 109a, 111b–13b; Makkot 3a–b, 5a, 8b, 11a, 12a, 13a, 14b, 16b–20a, 21a–22a, 23b; Shevuot 4b, 16a, 22b–23a, 25a, 34a, 44b, 49a; Avodah Zarah 9b, 12a–b, 13b, 20a, 34b, 36b, 42a, 43b, 44b, 45b, 51a–52a, 53b, 66a, 67b; Horayot 4b, 8a, 13a; Zevachim 7b, 9a, 12a, 29b, 34a, 36b, 45a, 49a, 50a, 52b, 55a, 60b, 62b, 76a, 85b, 97a, 104a, 106a, 107a–b, 112b, 114a–b, 117b–18a, 119a; Menachot 23a, 33b, 37b, 40b, 44b–45a, 65b–66a, 67a, 70b–71a, 77b, 78b, 81b–82a, 83a–b, 90b, 93a, 99b, 101b; Chullin 2a–142a; Bekhorot 4b, 6b–7a, 9b–10a, 11b–12a, 14b–15b, 19a, 21b, 23b, 25a, 26b, 27b–28a, 30a, 32a, 33a, 37a–b, 39a, 41a–b, 43a, 50b–51a, 53a–b, 54b, 56b; Arachin 7b, 28b–29a, 30b, 31b, 33a; Temurah 8a, 11b–12a, 17b, 18b, 21a–b, 28b, 31a; Keritot 3b, 4b, 21a, 24a, 27a; Meilah 13b, 15b–16a; Niddah 13a, 24a, 25a, 40a. Babylonia, 6th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Bavli. Edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr, Chaim Malinowitz, and Mordechai Marcus, 72 vols. Brooklyn: Mesorah Pubs., 2006.

Rashi

Medieval[]

- Deuteronomy Rabbah 4:1–11. Land of Israel, 9th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Leviticus. Translated by H. Freedman and Maurice Simon. London: Soncino Press, 1939. ISBN 0-900689-38-2.

- Exodus Rabbah 30:5, 16. 10th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Exodus. Translated by S. M. Lehrman. London: Soncino Press, 1939. ISBN 0-900689-38-2.

- Rashi. Commentary. Deuteronomy 11–16. Troyes, France, late 11th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., Rashi. The Torah: With Rashi’s Commentary Translated, Annotated, and Elucidated. Translated and annotated by Yisrael Isser Zvi Herczeg, 5:119–79. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1997. ISBN 0-89906-030-7.

- Judah Halevi. Kuzari. 3:40–41; 4:29. Toledo, Spain, 1130–1140. Reprinted in, e.g., Jehuda Halevi. Kuzari: An Argument for the Faith of Israel. Intro. by Henry Slonimsky, 173, 241. New York: Schocken, 1964. ISBN 0-8052-0075-4.

Maimonides

- Maimonides. Mishneh Torah, Intro.:3. Cairo, Egypt, 1170–1180.

- Maimonides. The Guide for the Perplexed, 1:24, 36, 38, 41, 54; 2:32; 3:17, 24, 29, 32, 39, 41, 42, 45, 46, 47, 48. Cairo, Egypt, 1190. Reprinted in, e.g., Moses Maimonides. The Guide for the Perplexed. Translated by Michael Friedländer, 34, 51, 54, 56, 77–78, 221, 288, 304–05, 317, 320, 323, 325, 339–40, 347, 351, 355, 357–358 358, 362, 366–67, 371. New York: Dover Publications, 1956. ISBN 0-486-20351-4.

- Zohar 1:3a, 82b, 157a, 163b, 167b, 184a, 242a, 245b; 2:5b, 20a, 22a, 38a, 40a, 89b, 94b, 98a, 121a, 124a, 125a–b, 128a, 148a, 168a, 174b; 3:7b, 20b, 104a, 206a, 296b. Spain, late 13th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., The Zohar. Translated by Harry Sperling and Maurice Simon. 5 vols. London: Soncino Press, 1934.

Modern[]

Hobbes

- Thomas Hobbes. Leviathan, 3:32, 36, 37; 4:44; Review & Conclusion. England, 1651. Reprint edited by C. B. Macpherson, 412, 461, 466–67, 476, 638, 724. Harmondsworth, England: Penguin Classics, 1982. ISBN 0140431950.

- Thomas Mann. Joseph and His Brothers. Translated by John E. Woods, 109. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005. ISBN 1-4000-4001-9. Originally published as Joseph und seine Brüder. Stockholm: Bermann-Fischer Verlag, 1943.

- Morris Adler. The World of the Talmud, 30. B'nai B'rith Hillel Foundations, 1958. Reprinted Kessinger Publishing, 2007. ISBN 0548080003.

- Martin Buber. On the Bible: Eighteen studies, 80–92. New York: Schocken Books, 1968.

- Jacob Milgrom. “‘You Shall Not Boil a Kid in Its Mother’s Milk’: An archaeological myth destroyed.” Bible Review. 1 (3) (Fall 1985): 48–55.

- Philip Goodman. "The Sukkot/Simhat Torah Anthology." Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1988. ISBN 0-8276-0010-0.

- Jacob Milgrom. "Ethics and Ritual: The Foundations of the Biblical Dietary Laws." In Religion and Law: Biblical, Jewish, and Islamic Perspectives, 159–91. Edited by E.B. Firmage. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns, 1989. ISBN 0931464390.

- Philip Goodman. "Passover Anthology." Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1992. ISBN 0827604106.

- Philip Goodman. "Shavuot Anthology." Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1992. ISBN 0827603916.

- Jacob Milgrom. “Food and Faith: The Ethical Foundations of the Biblical Diet Laws: The Bible has worked out a system of restrictions whereby humans may satiate their lust for animal flesh and not be dehumanized. These laws teach reverence for life.” Bible Review. 8 (6) (Dec. 1992).

- Kassel Abelson. “Official Use of ‘God.’” New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 1993. YD 278:12.1993. Reprinted in Responsa: 1991–2000: The Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Conservative Movement. Edited by Kassel Abelson and David J. Fine, 151–52. New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 2002. ISBN 0-916219-19-4.

- Aaron Wildavsky. Assimilation versus Separation: Joseph the Administrator and the Politics of Religion in Biblical Israel, 3–4. New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers, 1993. ISBN 1-56000-081-3.

- Jeffrey H. Tigay. The JPS Torah Commentary: Deuteronomy: The Traditional Hebrew Text with the New JPS Translation, 116–59, 446–70. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1996. ISBN 0-8276-0330-4.

- Jacob Milgrom. “Jubilee: A Rallying Cry for Today’s Oppressed: The laws of the Jubilee year offer a blueprint for bridging the gap between the have and have-not nations.” Bible Review. 13 (2) (Apr. 1997).

Steinsaltz

- Elliot N. Dorff and Aaron L. Mackler. “Responsibilities for the Provision of Health Care.” New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 1998. YD 336:1.1998. Reprinted in Responsa: 1991–2000: The Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Conservative Movement. Edited by Kassel Abelson and David J. Fine, 319, 321, 324. New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 2002. ISBN 0-916219-19-4. (the implications for our duty to provide medical care of following God and of our duty to aid the poor).

- Adin Steinsaltz. Simple Words: Thinking About What Really Matters in Life, 166. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1999. ISBN 068484642X.

- Alan Lew. This Is Real and You Are Completely Unprepared: The Days of Awe as a Journey of Transformation, 65–76. Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 2003. ISBN 0-316-73908-1.

- Jack M. Sasson. “Should Cheeseburgers Be Kosher? A Different Interpretation of Five Hebrew Words.” Bible Review 19 (6) (Dec. 2003): 40–43, 50–51.

- Nathaniel Philbrick. Mayflower: A Story of Courage, Community, and War, 309. New York: Viking Penguin, 2006. ISBN 0-670-03760-5. (Jubilee.)

- Naphtali S. Meshel. “Food for Thought: Systems of Categorization in Leviticus 11.” Harvard Theological Review 101 (2) (Apr. 2008): 203, 207, 209–13.

- Gloria London. “Why Milk and Meat Don’t Mix: A New Explanation for a Puzzling Kosher Law.” Biblical Archaeology Review. 34 (6) (Nov./Dec. 2008): 66–69.

- U.S. Department of State. Trafficking in Persons Report: June 2009.

External links[]

Texts[]

Commentaries[]

- Academy for Jewish Religion, New York

- American Jewish University

- Bar-Ilan University

- Chabad.org

- Jewish Theological Seminary

- Orthodox Union

- Rabbi Shmuel Herzfeld

- Reconstructionist Judaism

- Sephardic Institute

- Union for Reform Judaism

- United Hebrew Congregations of the Commonwealth

- United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism

| |||||||||||||||||||