| Himyarite Kingdom | |||||

| مملكة حِمْيَر | |||||

| |||||

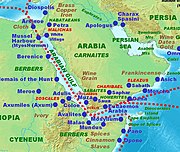

Himyarite Kingdom (red) in the 3rd century AD.

| |||||

| Capital | Zafar San‘a’ (poss. 500s) | ||||

| Languages | Himyarite | ||||

| Religion | Paganism Judaism Christianity | ||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||

| King | |||||

| - | 510s-520s | Dhu Nuwas | |||

| Historical era | Antiquity | ||||

| - | Established | 110 BC | |||

| - | Disestablished | 520s | |||

The "Homerite Kingdom" is described in the southern tip of the Arabian peninsula in the 1st century Periplus of the Erythraean Sea.

Coin of the Himyarite Kingdom. This is an imitation of a coin of Augustus. 1st Century CE.

The Himyarite Kingdom or Himyar (in Arabic مملكة حِمْيَر mamlakat ħimyâr), anciently called Homerite Kingdom by the Greeks and the Romans, was a state in ancient Yemen dating from 110 BC Taking the modern date city of Sanaa as its capital after the ancient city of Zafar. It conquered neighbouring Saba (Sheba) in c.25 BC, Qataban in c.200 CE and Hadramaut c.300 CE. Its political fortunes relative to Saba changed frequently until it finally conquered the Sabaean Kingdom around 280 CE.[1]

History[]

It was the dominant state in Arabia until 525 AD. The economy was based on agriculture. Foreign trade was based on the export of frankincense and myrrh. For many years it was also the major intermediary linking East Africa and the Mediterranean world. This trade largely consisted of exporting ivory from Africa to be sold in the Roman Empire. Ships from Himyar regularly traveled the East African coast, and the state also exerted a large amount of Influence both cultural religious and political to the trading cities of East Africa whilst the cities of East Africa remained independent. The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea describes the trading empire of Himyar and its ruler Charibael (Karab Il Watar Yuhan'em II), who is said to have been on friendly terms with Rome:

- ""23. And after nine days more there is Saphar, the metropolis, in which lives Charibael, lawful king of two tribes, the Homerites and those living next to them, called the Sabaites; through continual embassies and gifts, he is a friend of the Emperors.""

- ―Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, Paragraph 23.[2]

From 115 B.C. until 300 A.D.[]

During this period, the Kingdom of Himyar conquered the kingdom of Sheba and took Raydan/Zafar for its capital instead of Ma’rib. Its ruins still lie on Mudawwar Mountain near the town of "Yarim". During this period, they began to decline and fall. Their trade failed to a very great extent, firstly, because of the Nabetean domain over the north of Hijaz; secondly, because of the Roman superiority over the naval trade routes after the Roman conquest of Egypt, Syria and the north of Hijaz; and thirdly, because of intertribal warfare. Thanks to the three above-mentioned factors, families of Qahtan were disunited and scattered about all over Arabia.

From 300 AD until the advent of Islam in Yemen[]

This period witnessed a lot of disorder and turmoil. The great many foreign and civil wars cost the people of Yemen their independence. During this era, the Aksumites invaded Tihama & Najran for the first time in 340 AD, making use of the constant intra-tribal conflict of Hamdan and Himyar. The Aksumite occupation of Tihama and Najran lasted until 378 AD, whereafter Yemen expelled the Aksumites. After the Ma'rib Dam last Great Flood (450 or 451 AD) weakened Himyar further and led to its collapse.

In the fifth century, several kings of Himyar are known to have converted to Judaism. The political context was the position of Arabia between the competing empires of Christian Byzantium and Zoroastrian Persia. Neutrality, and good trade relations with both empires, was essential to the prosperity of the Arabian trade routes. Scholars speculate that the choice of Judaism may have been an attempt at maintaining neutrality.[3]

As the story has come down to us, about the year 500 AD, the King of Himyar, Abu-Kariba Assad, undertook a military expedition into northern Arabia in an effort to eliminate Byzantine influence. The Byzantine emperors had long eyed the Arabian Peninsula as a region in which to extend their influence, thereby to control the lucrative spice trade and the route to India. Without actually staging a conquest of the region, the Byzantines hoped to establish a protectorate over the pagan Arabs by converting them to Christianity. The cross would then bear commercial advantages as it did in Ethiopia. The Byzantines had made some progress in northern Arabia but had met with little success in Himyar.[3]

Abu-Kariba's forces reached Yathrib and, meeting no resistance and not expecting any treachery from the inhabitants, they passed through the city, leaving a son of the king behind as governor. Scarcely had Abu-Kariba proceeded farther, when he received news that the people of Yathrib had killed his son. Smitten with grief; he turned back in order to wreak bloody vengeance on the city. After cutting down the palm trees from which the inhabitants derived their main income, Abu-Kariba laid siege to the city. The Jews of Yathrib fought side by side with pagan fellow inhabitants to defend their town and harried the besiegers with sudden sallies. During the siege Abu-Kariba fell severely ill. Two Jewish scholars in Yathrib, Kaab and Assad by name, hearing of their enemy's misfortune, called on the king in his camp, and used their knowledge of medicine to restore him to health. While attending the king, they pleaded with him to lift the siege and make peace. The sages' appeal is said to have persuaded Abu-Kariba; he called off his attack and also embraced Judaism along with his entire army. At his insistence, the two Jewish savants accompanied the Himyarite king back to his capital, where he demanded that all his people convert to Judaism. Initially, there was great resistance, but after an ordeal had justified the king's demand and confirmed the "truth" of the Jewish faith, many Himyarites embraced Judaism. The conversions, however, were not total, and there remained as many pagans as Jews in the land. Such conversions, by ordeal, were not uncommon in Arabia. Some historians argue that the conversions occurred, not due to political motivations, but because Judaism, by its philosophical, simplistic and austere nature, was attractive to the nature of the Semitic people. In any case, it is known that by the 6th and 7th centuries, Judaism flourished in Himyar; and in inscriptions dating from those centuries Jewish religious terms such as "Rahman" ("the merciful," a divine epithet), "the god of Israel", and the "Lord of Judah" bears testament to this fact.[3]

Abu-Kariba's reign did not last long after his conversion to Judaism. His warlike nature prevented him from maintaining peace and prompted him to engage in bold enterprises. It is uncertain how Abu-Kariba met his death, although some scholars believe that his own soldiers, worn out by constant campaigning, killed him. He left three sons, Hasan, Amru, and Zorah, all of whom were minors at the time. After Abu-Kariba's demise, a pagan named Dhu-Shanatir seized the throne.[3]

[]

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding reliable references. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (October 2009) |

Himyar descendant of Pure Arabs: Who originated from the progeny of Ya‘rub bin Yashjub bin Qahtan.[4] They were also called Qahtanian Arabs.

- Himyar: The most famous of whose septs were Zaid Al-Jamhur, Banu Quda'a and Sakasic.

- Kahlan: The most famous of whose septs were Hamdan, Azd, Anmar, Tayy, Shammar, Midhhij, Kinda, Lakhm, Judham

Kahlan septs emigrated from Yemen to dwell in the different parts of the Arabian Peninsula prior to the Great Flood (Sail Al-‘Arim of Ma’rib Dam), due to the failure of trade under the Roman pressure and domain on both sea and land trade routes following Roman occupation of Egypt and Syria.

Naturally enough, the competition between Kahlan and Himyar led to the evacuation of the first and the settlement of the second in Yemen.

The emigrating septs of Kahlan can be divided into four groups:

- Azd: Who, under the leadership of ‘Imran bin ‘Amr Muzaiqbâ’, wandered in Yemen, sent pioneers and finally headed northwards. Details of their emigration can be summed up as follows:

- Tha‘labah bin ‘Amr left his tribe Al-Azd for Hijaz and dwelt between Tha‘labiyah and Dhi Qar. When he gained strength, he headed for Madinah where he stayed. Of his seed are Aws and Khazraj, sons of Haritha bin Tha‘labah.

- Haritha bin ‘Amr, known as Khuza‘a, wandered with his folks in Hijaz until they came to Mar Az-Zahran. , they conquered the Haram, and settled in Makkah after having driven away its people, the tribe of Jurhum.

- ‘Imran bin ‘Amr and his folks went to ‘Oman where they established the tribe of Azd whose children inhabited Tihama and were known as Azd-of-Shanu’a.

- Jafna bin ‘Amr and his family, headed for Syria where he settled and initiated the kingdom of Ghassan who was so named after a spring of water, in Hijaz, where they stopped on their way to Syria.

- Lakhm and Judham: Of whom was Nasr bin Rabi‘a, father of Manadhira, Kings of Heerah.

- Banu Tai’: Who also emigrated northwards to settle by the so- called Aja and Salma Mountains which were consequently named as Tai’ Mountains.

- Kindah: Who dwelt in Bahrain but were expelled to Hadramout and Najd where they instituted a powerful government but not for long, for the whole tribe soon faded away.

Another tribe of Himyar, known as Banu Quda'a, also left Yemen and dwelt in Samawa semi-desert on the borders of Iraq.

Language[]

The Himyarite language (Semitic, but not Sayhadic) was spoken in the south-western Arabian peninsula until the 10th century.

Kings of Saba' and Himyar[]

Template:Kings of Sheba and Himyar

See also[]

- Tub'a Abu Kariba As'ad

- Rulers of Sheba and Himyar

- Ancient history of Yemen

- Yemenite Jews

- Zafar, Himyar

References[]

Bibliography[]

- Alessandro de Maigret. Arabia Felix, translated Rebecca Thompson. London: Stacey International, 2002. ISBN 1-900988-07-0

- Andrey Korotayev. Ancient Yemen. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995. ISBN 0-19-922237-1.

- Andrey Korotayev. Pre-Islamic Yemen. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 1996. ISBN 3-447-03679-6.

- Bafaqīh, M. ‛A., L'unification du Yémen antique. La lutte entre Saba’, Himyar et le Hadramawt de Ier au IIIème siècle de l'ère chrétienne. Paris, 1990 (Bibliothèque de Raydan, 1).

- Yule, P., Himyar Late Antique Yemen/Die Spätantike im Jemen, Aichwald, 2007, ISBN 978-3-929290-35-6

- Yule, Zafar-The Capital of the Ancient Himyarite Empire Rediscovered, Jemen-Report 36, 2005, 22-29

- Joseph Adler, "The Jewish Kingdom of Himyar (Yemen): Its Rise and Fall" Midstream, May/June 2000, Volume XXXXVI, No. 4

External links[]

ar:مملكة حمير bg:Химярит fa:حمیر lt:Himjaras arz:حمير ru:Химьяр tr:Himyar Krallığı