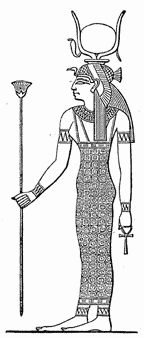

1888 illustration of Hathor

Hathor (ḥwt-ḥr, Egyptian for Horus's enclosure),[1] was an Ancient Egyptian goddess who personified the principles of love, motherhood and joy.[2] She was one of the most important and popular deities throughout the history of Ancient Egypt. Hathor was worshiped by royalty and common people alike in whose tombs she is depicted as “Mistress of the West” welcoming the dead into the next life.[3] In other roles she was a goddess of music, dance, foreign lands and fertility who helped women in childbirth,[3] as well as the patron goddess of miners.[4]

The cult of Hathor pre-dates the historical period and the roots of devotion to her are, therefore, difficult to trace, though it may be a development of predynastic cults who venerated the fertility, and nature in general, represented by cows.[5]

Hathor is commonly depicted as a cow goddess with head horns in which is set a sun disk with Uraeus. Twin feathers are also sometimes shown in later periods as well as a meant necklace.[5] Hathor may be the cow goddess who is depicted from an early date on the Narmer Palette and on a stone urn dating from the 1st dynasty that suggests a role as sky-goddess and a relationship to Horus who, as a sun god, is “housed” in her.[5]

The Ancient Egyptians viewed reality as multi-layered in which deities who merge for various reasons, whilst retaining divergent attributes and myths, were not seen as contradictory but complementary.[6] In a complicated relationship Hathor is at times the mother, daughter and wife of Ra and, like Isis, is at times described as the mother of Horus, and associated with Bastet.[5]

The cult of Osiris promised eternal life to those deemed morally worthy. Originally the justified dead, male or female, became an Osiris but by early Roman times females became identified with Hathor and men with Osiris.[7]

The ancient Greeks identified Hathor with the goddess Aphrodite and the Romans as Venus.[8]

Early depictions[]

Hathor is not unambiguously depicted until the 4th dynasty.[9] In the historical era Hathor is shown using the imagery of a cow deity. Artifacts from pre-dynastic times depict cow deities using the same symbolism as used in later times for Hathor and Egyptologists speculate that these deities may be one and the same or precursors to Hathor.[10]

A cow deity appears on the belt of the King on the Narmer Palette dated to the pre-dynastic era, and this may be Hathor or, in another guise, the goddess Bat with whom she is linked and later supplanted. At times they are regarded as one and the same goddess, though likely having separate origins, and reflections of the same divine concept. The evidence pointing to the deity being Hathor in particular is based on a passage from the Pyramid Texts which states that the Kings apron comes from Hathor.[11]

A stone urn recovered from Hierakonpolis and dated to the 1st dynasty has on its rim the face of a cow deity with stars on its ears and horns that may relate to Hathor's, or Bat's, role as a sky-goddess.[5] Another artifact from the 1st dynasty shows a cow lying down on an ivory engraving with the inscription "Hathor in the Marshes.." indicating her association with vegetation and the papyrus marsh in particular. From the Old Kingdom she was also called "Lady of the Sycamore" in her capacity as a tree deity.[5]

Relationships, associations, images and symbols[]

Hathor had a complex relationship with Ra, in one myth she is his eye and considered his daughter but later, when Ra assumes the role of Horus with respect to Kingship, she is considered Ra's mother. She absorbed this role from another cow goddess 'Mht wrt' ("Great flood") who was the mother of Ra in a creation myth and carried him between her horns. As a mother she gave birth to Ra each morning on the eastern horizon and as wife she conceives through union with him each day.[5]

Hathor along with the goddess Nut was associated with the Milky Way during the third millennium BCE when, during the fall and spring equinoxes, it aligned over and touched the earth where the sun rose and fell.[12] The four legs of the celestial cow represented Nut or Hathor could, in one account, be seen as the pillars on which the sky was supported with the stars on their bellies constituting the milky way on which the solar barque of Ra, representing the sun, sailed.[13] An alternate name for Hathor, which persisted for 3,000 years, was Mehturt (also spelt Mehurt, Mehet-Weren't, and Mehet-uret), meaning 'great flood, a direct reference to her being the milky way. The Milky Way was seen as a waterway in the heavens, sailed upon by both the sun deity and the moon, leading the ancient Egyptians to describe it as The Nile in the Sky. Due to this, and the name mehturt, she was identified as responsible for the yearly inundation of the Nile. Another consequence of this name is that she was seen as a herald of imminent birth, as when the amniotic sac breaks and floods its waters, it is a medical indicator that the child is due to be born extremely soon. Another interpretation of the Milky Way was that it was the primal snake, Wadjet, the protector of Egypt who was closely associated with Hathor and other early deities among the various aspects of the great mother goddess, including Mut and Naunet. Hathor also was favoured as a protector in desert regions. Hathor's identity as a cow, perhaps depicted as such on the Narmer Palette, meant that she became identified with another ancient cow-goddess of fertility, Bat. It still remains an unanswered question amongst Egyptologists as to why Bat survived as an independent goddess for so long. Bat was, in some respects, connected to the Ba, an aspect of the soul, and so Hathor gained an association with the afterlife. It was said that, with her motherly character, Hathor greeted the souls of the dead in Duat, and proffered them with refreshments of food and drink. She also was described sometimes as mistress of the necropolis. The assimilation of Bat, who was associated with the sistrum, a musical instrument, brought with it an association with music. In this later form, Hathor's cult became centred in Dendera in Upper Egypt and it was led by priestesses and priests who also were dancers, singers, and other entertainers.

Hathor also became associated with the meant, the turquoise musical necklace often worn by women. A hymn to Hathor says:

- Thou art the Mistress of Jubilation, the Queen of the Dance, the Mistress of Music, the Queen of the Harp Playing, the Lady of the Choral Dance, the Queen of Wreath Weaving, the Mistress of Inebriety Without End.

Essentially, Hathor had become a goddess of joy, and so she was deeply loved by the general population, and truly revered by women, who aspired to embody her multifaceted role as wife, mother, and lover. In this capacity, she gained the titles of Lady of the House of Jubilation, and The One Who Fills the Sanctuary with Joy. The worship of Hathor was so popular that a lot of festivals were dedicated to her honor than any other Egyptian deity, and more children were named after this goddess than any other deity. Even Hathor's priesthood was unusual, in that both women and men became her priests.

In recent years, the theory of matriarchal cultures existing in profusion before 3,000 BCE has taken root and brought into question the interpretation of Hathor as only wife or only mother. Hathor wears the head-dress of eighteen serpents (traditionally associated with wisdom and women), the cows horns (horns were associated with the crescent moon and thus, a woman's menstrual cycles). Hathor may have, quite possibly, been the original mother goddess of Egypt.

Temples[]

As Hathor's cult developed from prehistoric cow cults it is not possible to say conclusively where devotion to her first took place. Dendera in Upper Egypt was a significant early site where she was worshiped as "Mistress of Dendera". From the Old Kingdom era she had cult sites in Meir and Kusae with the Giza-Saqqara area perhaps being the centre of devotion. At the start of the first Intermediate period Dendera appears to have become the main cult site where she was considered to be the mother as well as the consort of "Horus of Edfu". Deir el-Bahri, on the west bank of Thebes, was also an important site of Hathor that developed from a pre-existing cow cult.[5]

Temples (and chapels) dedicated to Hathor:

- The Temple of Hathor and Maat at Deir el-Medina, West Bank, Luxor.

- The Temple of Hathor at Philae Island, Aswan.

- The Hathor Chapel at the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut. WestBank, Luxor.

Bloodthirsty warrior[]

The Middle Kingdom was founded when Upper Egypt's pharaoh, Mentuhotep II, took control over Lower Egypt, which had become independent during the First Intermediate Period, by force. This unification had been achieved by a brutal war that was to last some twenty-eight years with many casualties, but when it ceased, calm returned, and the reign of the next pharaoh, Mentuhotep III, was peaceful, and Egypt once again became prosperous. A tale, (see "The Book of the Heavenly Cow"), from the perspective of Lower Egypt, developed around this experience of protracted war. In the tale following the war, Ra (representing the pharaoh of Upper Egypt) was no longer respected by the people (of Lower Egypt) and they ceased to obey his authority. The myth states that Ra communicated through Hathor's third Eye (Maat) and told her that some people in the land were planning to assassinate him. Hathor was so angry that the people she had created would be audacious enough to plan that, that she became Sekhmet (war goddess of Upper Egypt) to destroy them. Hathor (as Sekhmet) became bloodthirsty and the slaughter was great because she could not be stopped. As the slaughter continued, Ra saw the chaos down below and decided to stop the blood-thirsty Sekhmet. So he poured huge quantities of blood-coloured beer on the ground to trick Sekhmet. She drank so much of it—thinking it to be blood—that she became drunk and returned to her former gentle self as Hathor.

Wife of Thoth[]

When Horus became identified as Ra in the changing Egyptian pantheon, under the name Ra-Horakhty, Hathor's position became unclear, since in later myths she had been the wife of Ra, but in earlier myths she was the mother of Horus. Many attempts to solve this gave Ra-Horakhty a new wife, Ausaas, to solve this issue around who was Ra-Horakhty's wife and Hathor became identified only as the mother of the new sun god. However, this left open the unsolved question of how Hathor could be his mother, since this would imply that Ra-Horakhty was a child of Hathor, rather than a creator. Such inconsistencies developed as the Egyptian pantheon changed over the thousands of years becoming very complex, and some were never resolved. In areas where the cult of Thoth became strong, Thoth was identified as the creator, leading to it being said that Thoth was the father of Ra-Horakhty, thus in this version Hathor, as the mother of Ra-Horakhty, was referred to as Thoth's wife. In this version of what is called the Ogdoad cosmogeny, Ra-Herakhty was depicted as a young child, often referred to as Neferhor. When considered the wife of Thoth, Hathor often was depicted as a woman nursing her child. Since Seshat had earlier been considered to be Thoth's wife, Hathor began to be attributed with many of Seshat's features. Since Seshat was associated with records and with acting as witness at the judgment of souls in Duat, these aspects became attributed to Hathor, which, together with her position as goddess of all that was good, lead to her being described as the (one who) expels evil, which in Egyptian is Nechmetawaj (also spelled Nehmet-awai, and Nehmetawy). Nechmetawaj can also be understood to mean (one who) recovers stolen goods, and so, in this form, she became goddess of stolen goods. Outside the Thoth cult during these times, it was considered important to retain the position of Ra-Herakhty (i.e. Ra) as self-created (via only the primal forces of the Ogdoad). Consequently, Hathor could not be identified as Ra-Herakhty's mother. Hathor's role in the process of death, that of welcoming the newly dead with food and drink, lead, in such circumstances, to her being identified as a jolly wife for Nehebkau, the guardian of the entrance to the underworld and binder of the Ka. Nevertheless, in this form, she retained the name of Nechmetawaj, since her aspect as a returner of stolen goods was so important to society that it was retained as one of her roles. Hathor votive faience balls are usually associated with this deity although the precise significance of their relationship remains unknown.

Hesat[]

In Egyptian mythology, Hesat (also spelt Hesahet, and Hesaret) was the manifestation of Hathor, the divine sky-cow, in earthly form. Like Hathor, she was seen as the wife of Ra.

Since she was the more earthly cow-goddess, Milk was said to be the beer of Hesat, a rather meaningless phrase as Hesat means milk anyway. As a dairy cow, Hesat was seen as the wet-nurse of the other gods, the one who creates all nourishment. Thus she was pictured as a divine white cow, carrying a tray of food on her horns, with milk flowing from her udders.

In this earthly form, she was, dualistically, said to be the mother of Anubis, the god of the dead, since, it is she, as nourisher, that brings life, and Anubis, as death, that takes it. Since Ra's earthly manifestation was the Mnevis bull, the three of Anubis as son, the Mnevis as father, and Hesat as mother, were identified as a family triad, and worshipped as such.

Hathor outside the Nile river in Egypt[]

Hathor was worshipped in Canaan in the eleventh century BCE, which at that time was ruled by Egypt, at her holy city of Hazor, or Tel Hazor which the Old Testament claims was destroyed by Joshua (Joshua 11:13, 21).

A major temple to Hathor was constructed by Seti II at the copper mines at Timna in Edomite Seir. Serabit el-Khadim (Arabic: سرابت الخادم) (Arabic, also transliterated Serabit al-Khadim, Serabit el-Khadem) is a locality in the south-west Sinai Peninsula where turquoise was mined extensively in antiquity, mainly by the ancient Egyptians. Archaeological excavation, initially by Sir Flinders Petrie, revealed the ancient mining camps and a long-lived Temple of Hathor. The Greeks, who became rulers of Egypt for three hundred years before the Roman domination in 31BCE, also loved Hathor and equated her with their own goddess of love and beauty, Aphrodite.

Notes[]

- ↑ "Hathor and Thoth: two key figures of the ancient Egyptian religion", Claas Jouco Bleeker, p22-102, BRILL, 1973, ISBN 9789004037342

- ↑ ”The ancient Egyptian pyramid texts”, Peter Der Manuelian, Translated by James P. Allen, p432, BRILL, 2005, ISBN 9004137777 (also commonly translated as “House of Horus”)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Lorna Oakes, Southwater, p157-159, ISBN 1-84476-279-3

- ↑ "Spotlights on the Exploitation and Use of Minerals and Rocks through the Egyptian Civilization". Egypt State Information Service. 2005. http://www.sis.gov.eg/En/Pub/magazin/spring1997/110204000000000008.htm. Retrieved 2010-04-20.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 "Oxford Guide to Egyptian Mythology", Donald B. Redford (Editor), p157-161, Berkley Reference, 2003, ISBN 0-425-19096-X

- ↑ Oxford Guide to Egyptian Mythology", Donald B. Redford (Editor), p106, Berkley Reference, 2003, ISBN 0-425-19096-X

- ↑ "Oxford Guide to Egyptian Mythology", Donald B. Redford (Editor), p.172, Berkley Reference, 2003, ISBN 0-425-19096-X

- ↑ "Isis in the Ancient World", Reginald Eldred Witt, p125, JHU Press, 1997 ISBN 0801856426

- ↑ "Early Dynastic Egypt: Strategies, Society and Security", Toby A. H. Wilkinson, p312, Routledge, 2001,ISBN 0415260116

- ↑ "Religion in ancient Egypt: gods, myths, and personal practice", Byron Esely Shafer, John Baines, Leonard H. Lesko, David P. Silverman, p24 Fordham University, Taylor & Francis, 1991, ISBN 0415070309

- ↑ "Early Dynastic Egypt: Strategies, Society and Security", Toby A. H. Wilkinson, p283, Routledge, 2001,ISBN 0415260116

- ↑ "Searching for ancient Egypt: art, architecture, and artifacts from the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology", University of Pennsylvania. Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, David P. Silverman, Edward Brovarski, p41, Cornell University Press, 1997, ISBN 0801434823

- ↑ "The tree of life: an archaeological study", E. O. James, p66, BRILL, 1967, ISBN 9004016120

External links[]

| |||||||||||||||||

| This page uses content from the English Wikipedia. The original article was at Hathor. The list of authors can be seen in the page history. |