The giants Fafner and Fasolt seize Freyja in Arthur Rackham's illustration of Richard Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen.

The mythology and legends of many different cultures include monsters of human appearance but prodigious size and strength. "Giant" is the English word (coined 1297) commonly used for such beings, derived from one of the most famed examples: the gigantes (Greek "γίγαντες"[1]) of Greek mythology.

In various Indo-European mythologies, gigantic peoples are featured as primeval creatures associated with chaos and the wild nature, and they are frequently in conflict with the gods, be they Olympian, Nartian, Hindu or Norse.

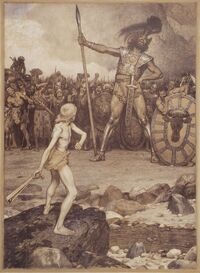

There are also accounts of giants in the Old Testament, most famously Goliath. Attributed to them are extraordinary strength and physical proportions.

Fairy tales such as Jack the Giant Killer have formed our modern perception of giants as stupid and violent monsters, sometimes said to eat humans, especially children (though this is actually a confusion with ogres, which are distinctly cannibalistic). The ogre in Jack and the Beanstalk is often described as a giant. However, in some more recent portrayals, like those of Roald Dahl, some giants are both intelligent and friendly, as in Gulliver's Travels.

Religious literature and beliefs[]

David faces Goliath in this 1888 lithograph by Osmar Schindler.

Jewish scriptures[]

The Bible (Genesis 6:4-5) tells of giants called Nephilim before and after the Flood:

"4 The Nephilim were on the earth in those days - and also afterward when the sons of God would consort with the daughters of man, who would bear to them. They were the mighty who, from old, were men of devastation. 5 God saw that the wickedness of Man was great upon the earth, and that every product of the thoughts of his heart was but evil always."

The nephilim were presumably destroyed in the Flood, but further giants are reported in the Torah, including the Anakites (Numbers 13:28-33), the Emites (Deuteronomy 2:10), and, in Joshua, the Rephaites (Joshua 12:4).

The Bible also tells of Gog and Magog, who later entered into European folklore, and of the famous battle between David and the Philistine giant Goliath. The 1st century historian Josephus, and the 1st-2nd century BCE Dead Sea Scrolls give Goliath's height as "four cubits and a span," approximately 2.00 m or about six feet seven inches.[2]

Christian scriptures[]

"There were giants on the earth in those days; and also after that, when the sons of God came in unto the daughters of men, and they bare children to them, the same became mighty men which were of old, men of renown." Genesis 6:4 (KJV).

The King James Bible (KJV) reports the giant Goliath as "six cubits and a span" in height—over nine feet tall, (over 2.75 m) (1 Samuel 17:4 KJV), but the Septuagint, a Greek Bible, also gives Goliath's height as "four cubits and a span" (~2.00 m).

Hinduism[]

In Hinduism, the giants are called Daityas. The Daityas (दैत्य) were the children of Diti and the sage Kashyapa who fought against the gods or Devas because they were jealous of their Deva half-brothers. Since Daityas were a power-seeking race, they sometimes allied with other races having similar ideology namely Danavas and Asuras. Daityas along with Danavas and Asuras are sometimes called Rakshasas, the generic term for a demon in Hindu mythology. Some known Daityas include Hiranyakashipu and Hiranyaksha. The main antagonist of the Hindu epic Ramayana, Ravana, was a Brahmin from his father's side and a Daitya from his mother's side. His younger brother Kumbhakarna was said to be as tall as a mountain and was quite good natured.

Hercules faces the giant Antaios in this illustration on a calix krater, c. 515–510 BCE.

Greek mythology[]

In Greek mythology the gigantes (γίγαντες) were (according to the poet Hesiod) the children of Uranus (mythology) (Ουρανός) and Gaea (Γαία) (spirits of the sky and the earth). They were involved in a conflict with the Olympian gods called the Gigantomachy (Γιγαντομαχία), which was eventually settled when the hero Heracles decided to help the Olympians. The Greeks believed some of them, like Enceladus, to lay buried from that time under the earth and that their tormented quivers resulted in earthquakes and volcanic eruptions.

Herodotus in Book 1, Chapter 68, describes how the Spartans uncovered in Tegea the body of Orestes which was seven cubits long—around 10 feet. In his book The Comparison of Romulus with Theseus Plutarch describes how the Athenians uncovered the body of Theseus, which was of more than ordinary size. The kneecaps of Ajax were exactly the size of a discus for the boy's pentathlon, wrote Pausanias. A boy's discus was about twelve centimeters in diameter, while a normal adult patella is around five centimeters, suggesting Ajax may have been around 14 feet (~4.3 meters) tall.

The Cyclopes, usually children of gods (Olympians) and nature spirits (nereids, naiads and dryads), are also compared to giants due to their huge size (Polyphemus, son of Poseidon and Thoosa, and nemesis of Odysseus and Jason, comes to mind).

Roman mythology[]

Several Jupiter-Giant-Columns have been found in Germania Superior. These were crowned with a statue of Jupiter, typically on horseback, defeating or trampling down a giant, often depicted as a snake. They are restricted to the area of south-western Germany, western Switzerland, French Jura and Alsace.

Norse mythology[]

In Norse mythology, the Jotun (jötnar in Old Norse, a cognate with ettin) are often opposed to the gods. While often translated as "giants", most are described as being roughly human sized. Some are portrayed as huge, such as frost giants (hrímþursar), fire giants (eldjötnar), and mountain giants (bergrisar).

The giants are the origin of most of various monsters in Norse mythology (e.g. the Fenrisulfr), and in the eventual battle of Ragnarök the giants will storm Asgard and defeat them in war. Even so, the gods themselves were related to the giants by many marriages, and there are giants such as Ægir, Loki, Mímir and Skaði, who bear little difference in status to them.

Norse mythology also holds that the entire world of men was once created from the flesh of Ymir, a giant of cosmic proportions, which name is considered by some to share a root with the name Yama of Indo-Iranian mythology.

An old Icelandic legend says that two night-prowling giants, a man and a woman, were traversing the fjord near Drangey Island with their cow when they were surprised by the bright rays of daybreak. As a result of exposure to daylight, all three were turned into stone. Drangey represents the cow and Kerling (supposedly the female giant, the name means "Old Hag") is to the south of it. Karl (the male giant) was to the north of the island, but he disappeared long ago.

A bergrisi appears as a supporter on the coat of arms of Iceland.

Balt mythology[]

According to Balt legends, the playing of a girl giantess named Neringa on the seashore formed the Curonian Spit ("neria, nerge, neringia" means land which is diving up and down like a swimmer). This giant child also appears in other myths (in some of which she is shown as a young strong woman, similar to a female version of the Greek Heracles). "Neringa" is the name of a modern town on the spot.

Bulgarian mythology[]

In Bulgarian mythology, giants called ispolini inhabited the Earth before modern humans. They lived in the mountains, fed on raw meat and often fought against dragons. Ispolini were afraid of blackberries which posed a danger of tripping and dying, so they offered sacrifices to that plant.[3]

Basque mythology[]

Giants are rough but generally righteous characters of formidable strength living up the hills of the Basque Country. Giants stand for the Basque people reluctant to convert to Christianity who decide to stick to the old life style and customs in the forest. Sometimes they hold the secret of ancient techniques and wisdom unknown to the Christians, like in the legend of San Martin Txiki, while their most outstanding feature is their strength. It follows that in many legends all over the Basque territory the giants are held accountable for the creation of many stone formations, hills and ages-old megalithic structures (dolmens, etc.), with similar explanations provided in different spots.

However, giants show different variants and forms, they are most frequently referred to as jentilak and mairuak, while as individuals they can be represented as Basajaun ('the lord of the forests'), Sanson (development of the Biblical Samson), Errolan (based on Roland, general of Charlemagne's army who fell dead at the Battle of Roncevaux Pass) or even Tartalo (a one-eyed giant akin to the Greek Cyclops).

Other[]

King Arthur faces a giant in this engraving by Walter Crane.

In folklore from all over Europe, giants were believed to have built the remains of previous civilizations. Saxo Grammaticus, for example, argues that giants had to exist, because nothing else would explain the large walls, stone monuments, and statues that we now know were the remains of Roman construction. Similarly, the Old English poem Seafarer speaks of the high stone walls that were the work of giants. Even natural geologic features such as the massive basalt columns of the Giant's Causeway on the coast of Northern Ireland were attributed to construction by giants. Giants provided the least complicated explanation for such artifacts.

Medieval romances such as Amadis de Gaula feature giants as antagonists, or, rarely, as allies. This is parodied famously in Cervantes' Don Quixote, when the title character attacks a windmill, believing it to be a giant. This is the source of the phrase tilting at windmills.

Tales of combat with giants were a common feature in the folklore of Wales, Scotland and Ireland. Celtic giants also figure in Breton and Arthurian romances perhaps as a reflection of the Nordic and Slavic mythology that arrived on the boats, and from this source they spread into the heroic tales of Torquato Tasso, Ludovico Ariosto, and their follower Edmund Spenser. In the small Scottish village of Kinloch Rannoch, a local myth to this effect concerns a local hill that apparently resembles the head, shoulders, and torso of a man, and has therefore been termed 'the sleeping giant'. Apparently the giant will awaken only if a specific musical instrument is played near the hill. Other giants, perhaps descended from earlier Germanic mythology, feature as frequent opponents of Dietrich von Bern in medieval German tales - in later portrayals Dietrich himself and his fellow heroes also became giants.

Many giants in English folklore were noted for their stupidity.[4] A giant who had quarreled with the Mayor of Shrewsbury went to bury the city with dirt; however, he met a shoemaker, carrying shoes to repair, and the shoemaker convinced the giant that he had worn out all the shoes coming from Shrewsbury, and so it was too far to travel.[5]

Other English stories told of how giants threw stones at each other. This was used to explain many great stones on the landscape.[6]

Giants figure in a great many fairy tales and folklore stories, such as Jack the Giant Killer, The Giant Who Had No Heart in His Body, Nix Nought Nothing, Robin Hood and the Prince of Aragon, Young Ronald, and Paul Bunyan. Ogres and trolls are humanoid creatures, sometimes of gigantic stature, that occur in various sorts of European folklore. An example of another, Slavic, folklore giant is Rübezahl, a kind giant from Wendish folklore who lived in the Giant Mountains (nowadays on the Czech-Polish border).

In Kalevala, Antero Vipunen is a giant shaman that possesses mighty spells dating to the creation. Epic hero Väinämöinen sets out to learn these spells from him, but Vipunen is buried underground, and when Väinämöinen digs him out, he is accidentally swallowed by Vipunen. Väinämöinen then forces Vipunen to submit and sing the spells out by hammering his insides. An analysis by Martti Haavio is that Vipunen is not physically large, but his familiar animal (astral form) is a whale. The depiction is not found in the majority of Finnish original stories, and most probably originates from the book's compiler Elias Lönnrot.[7]

William Cody's autobiography refers to a Pawnee Indian legend: "While we were in the sandhills, scouting the Niobrara country, the Pawnee Indians brought into camp some very large bones, one of which the surgeon of the expedition pronounced to be the thigh bone of a human being. The Indians said the bones were those of a race of people who long ago had lived in that country. They said these people were three times the size of a man of the present day, that they were so swift and strong that they could run by the side of a buffalo, and, taking the animal in one arm, could tear off a leg and eat it as they ran."[8]

Names and tribal origin of giants[]

|

|

|

Notes[]

- ↑ γίγαντες, Georg Autenrieth, A Homeric Dictionary, on Perseus Digital Library

- ↑ Variants of Bible Manuscripts

- ↑ Стойнев, Анани; Димитър Попов, Маргарита Василева, Рачко Попов (2006). "Исполини" (in Bulgarian). Българска митология. Енциклопедичен речник. изд. Захари Стоянов. pp. 147–148. ISBN 954-739-682-X.

- ↑ K. M. Briggs, The Fairies in English Tradition and Literature, p 63 University of Chicago Press, London, 1967

- ↑ K. M. Briggs, The Fairies in English Tradition and Literature, p 64 University of Chicago Press, London, 1967

- ↑ K. M. Briggs, The Fairies in English Tradition and Literature, p 65 University of Chicago Press, London, 1967

- ↑ http://www.parkkinen.org/vipunen.html

- ↑ The Life of Buffalo Bill (page 207), by William Cody

References[]

- Dictionary of Hindu Lore and Legend (ISBN 0-500-51088-1) by Anna Dhallapiccola

- Lyman, Robert R., Sr. (1971). Forbidden Land: Strange Events in the Black Forest. Vol. 1. Coudersport, PA: Potter Enterprise.

- Childress, David Hatcher (1992). Lost Cities of North & Central America. Stelle, IL: Adventures Unlimited.

| This page uses content from the English Wikipedia. The original article was at Giant (mythology). The list of authors can be seen in the page history. |