The New Testament missionary outreach of the Christian church from the time of St Paul was extensive throughout the Roman Empire. During the Middle Ages the Christian monasteries and missionaries such as Saint Patrick, and Adalbert of Prague propagated learning and religion beyond the boundaries of the old Roman Empire. In the 7th century Gregory the Great sent missionaries including Augustine of Canterbury into England. During the Age of Discovery, the Roman Catholic Church established a number of Missions in the Americas and other colonies through the Augustinians, Franciscans and Dominicans in order to spread Christianity in the New World and to convert the Native Americans and other indigenous people. At the same time, missionaries such as Francis Xavier as well as other Jesuits, Augustinians, Franciscans and Dominicans were moving into Asia and the far East. The Portuguese sent missions into Africa. These are some of the most well-known missions in history. While some of these missions were associated with imperialism and oppression, others (notably Matteo Ricci's Jesuit mission to China) were relatively peaceful and focused on integration rather than cultural imperialism.

As the church normally organizes itself along territorial lines, and because they had the human and material resources, religious orders--some even specializing in it--undertook most missionary work, especially in the early phases. Over time a normalised church structure was gradually established in the mission area, often starting with special jurisdictions known as apostolic prefectures and apostolic vicariates. These developing churches eventually intended 'graduating' to regular diocesan status with a local episcopacy appointed, especially after decolonization, as the church structures often reflect the political-administrative reality.

Jesuit mission to China[]

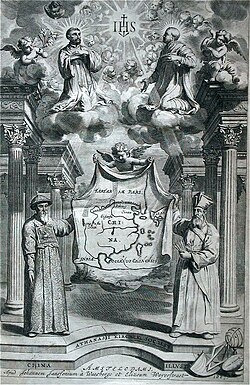

Above: Francis Xavier (left), Ignatius of Loyola (right) and Christ at the upper center. Below: Matteo Ricci (right) and Xu Guangqi (left), all in dialogue towards the evangelization of China.

The history of the missions of the Jesuits in China in the early modern era stands as one of the notable events in the early history of relations between China and the Western world, as well as a prominent example of relations between two cultures and belief systems in the pre-modern age. The missionary efforts and other work of the Society of Jesus, or Jesuits between the 16th and 17th century played a significant role in introducing Western knowledge, science, and culture to China. Their work laid much of the foundation for much of Christian culture in Chinese society today. Members of the Jesuit delegation to China were perhaps the most influential Christian missionaries in that country between the earliest period of the religion up until the 19th century, when significant numbers of Catholic and Protestant missions developed.

The first attempt by Jesuits to reach China was made in 1552 by St. Francis Xavier, Spanish priest and missionary and founding member of the Society. Xavier, however, died the same year on the Chinese island of Shangchuan, without having reached the mainland. Three decades later, in 1582, led by several figures including the prominent Italian Matteo Ricci, Jesuits once again initiated mission work in China, ultimately introducing Western science, mathematics, astronomy, and visual arts to the imperial court, and carrying on significant inter-cultural and philosophical dialogue with Chinese scholars, particularly representatives of Confucianism. At the time of their peak influence, members of the Jesuit delegation were considered some of the emperor's most valued and trusted advisors, holding numerous prestigious posts in the imperial government. Many Chinese, including notable former Confucian scholars, adopted Christianity and became priests and members of the Society of Jesus.

The Jesuits in China[]

The Jesuits first arrived in China in 1574. The Jesuits were men whose vision went far beyond the Macao status quo, priests serving churches on the fringes of a pagan society. They were possessed by a dream - the creation of a Sino-Christian civilization that would match the Roman-Christian civilization of the West.

This unique approach was largely the outworking of two Italian Jesuits, Michele Ruggieri (1543-1607) and Matteo Ricci (1552-1610). Both were determined to adapt to the religious qualities of the Chinese: Ruggieri to the common people, in whom Buddhist and Taoist elements predominated, and Ricci to the educated classes, where Confucianism prevailed.

By (1610) more than two thousand Chinese from all levels of society had confessed their faith in Jesus Christ.

Jesuits in China

Clark has summarized as follows:

"When all is said and done, one must recognize gladly that the Jesuits made a shining contribution to mission outreach and policy in China. They made no fatal compromises, and where they skirted this in their guarded accommodation to the Chinese reverence for ancestors, their major thrust was both Christian and wise. They succeeded in rendering Christianity at least respectable and even credible to the sophisticated Chinese, no mean accomplishment."[1]

The Jesuits succeeded in planting a Chinese church that has stood the test of time. "By 1844, Roman Catholics may have totalled 240,000; in 1901 the figure reached 720,490".[2] However, one should not overlook the fact that the Jesuit financial policy grievously aggravated the difficulties of that Church. Their missionaries involved themselves in business ventures of various sorts; they became the landlords of income-producing properties, developed the silk industry for Western trade, and organized money-lending operations on a large scale. All these eventually generated misunderstanding and tension between the foreign community and the Chinese people. The Communists held this against them as late as the mid-twentieth century.

Scientific exchange[]

"Life and works of Confucius", by Father Prospero Intorcetta, 1687.

The Jesuits introduced Western science and astronomy, then undergoing its own revolution, to China. "Jesuits were accepted in late Ming court circles as foreign literati, regarded as impressive especially for their knowledge of astronomy, calendar-making, mathematics, hydraulics, and geography."[3] This influence worked in both directions: Template:Long quotation

The Jesuits were very active in transmitting Chinese knowledge to Europe, such as translating Confucius's works into European languages. Ricci had already started to report on the thoughts of Confucius, and Father Prospero Intorcetta published the life and works of Confucius in Latin in 1687.[4] It is thought that such works had considerable importance on European thinkers of the period, particularly those who were interested by the integration of the system of morality of Confucius into Christianity.[5][6]

Franciscan missions to the Maya[]

The Franciscan Missions to the Maya were the attempts of the Franciscans to Christianize the indigenous people of the new world, specifically the Maya. They began to take place soon after the discovery of the New World made by Christopher Columbus in 1492, which opened the door for Catholic missions. As early as 1519 there are records of Franciscan activity in the American continent, and throughout the early 16th Century the mission movement spreads from the original contact point in the Caribbean to include Mexico, Central America, parts of South America, and the Southwest United States.[7]

The goal of the Franciscan missions was to spread the Christian faith to the “uncivilized” people of the New World through “word and example”,[8] but also, though not explicitly stated, oppression and castigation, specifically self-flagellation, also known as mortification of the flesh. Their attempts, however, resulted in much violence and cruelty.

Purpose[]

Spreading Christianity to the newly discovered continent was a top priority, but only one piece of the Spanish colonization system. The influence of the Franciscans, considering that missionaries are sometimes seen as tools of imperialism,[9] enabled other objectives to be reached, such as the extension of Spanish language, culture and political control to the New World. A goal was to change the agricultural or nomadic Indian into a model of the Spanish people and society. Basically, the aim was for urbanization. The missions achieved this by “offering gifts and persuasion…and safety from enemies.” This protection was also security for the Spanish military operation, since there would be theoretically less warring if the natives were pacified, thus working with another piece of the system.[10]

Methods in the Yucatan[]

Franciscan influence in the Yucatan can be considered unique because they enjoyed sole access to the area; no other religious orders, such as the Jesuits or the Dominicans were competing for the territory.[11] Essentially, this meant that there was no one to defy the goings-on of the Franciscans at this time. They were able to use whatever method they deemed necessary to spread their beliefs, although at the beginning they tried to follow the “conversion programme” that had already been used in Mexico.[12]

Word and example[]

The original method of instruction of the ‘new faith’ to the Maya was very straightforward and simple. “Word and example” would be all they need to show these people the then-believed error of their ways and follow Christianity.[13] An example of how the Franciscans carried out this belief can be seen by the actions of Fray Martín de Valencia, one of the Twelve Apostles of Mexico. Upon arrival to his province, he kneeled before a group of assembled natives and began to speak publicly of his own sins [a form of confession], and commenced to whip himself in front of all. Thus the ideal method of teaching was to avoid “direct exercise of power.”[13]

Education of youth[]

Another means of conversion was the education of the Mayan youth. Through the aforementioned conversion programme, “sons of the nobles were taken into monastery schools and there taught until they were judged sufficiently secure in the faith to be returned to their villages as Christian schoolmasters, where they were to lead their fellow villagers through simple routines of worship.”[12] According to Fray Diego de Landa in his book Relación de las cosas de Yucatán, this program was quite successful, and an “admirable thing to see.”[14]

Physical punishment[]

The early success through peaceful teaching and quiet example of the Franciscan missionaries, however, was short lived. Within the first few years it became apparent that verbal teaching would not be enough, as the Mayans remained overall unmoved of the lessons of Christianity.[15] In 1539 the heads of the three religious orders operating in Mexico met with the Franciscan bishop Juan de Zumárraga and concluded that the friars of the missionaries could legally inflict “light punishment” on the Mayans.[15] These moderate disciplines, however, soon turned into cases of physical abuse and excessive cruelty; it seems that once the friars found this method to be successful, there could be no turning back. This can be witnessed by the words of Vasco de Quiroga, a bishop of Michoacán: “[the regular orders] are now inflicting many mistreatments upon the Indians, with great haughtiness and cruelty, for when the Indians do not obey them, they insult and strike them, tear out their hair, have them stripped and cruelly flogged, and then throw them into prison in chains and cruel irons.”[16]

Mayan Retaliations[]

Cochua and Chetumal[]

Because of extreme cruelties inflicted upon the Mayan people of the provinces Cochua and Chetumal, a rebellion broke out. The violence includes several citizens burned alive in their homes, the hanging of women from branches, with their children then hanged from their feet, and another instance of hanging virgins simply for their beauty.[17] While de Landa does not go into details of what the Mayans did to the Spaniards, he certainly graphically explains the Spanish retribution: “the Spaniards pacified them… [by] cutting off noses, arms and legs, and the breasts of women; throwing them into deep lagoons with gourds tied to their feet; stabbing the little children because they did not walk as fast as their mothers.”[18]

Valladolid[]

An additional rebellion was executed by the Indians of Valladolid. During this rebellion, which took place in 1546, many Spaniards were killed, as well as native converts loyal to their masters. Livestock from Spain was razed, and Spanish tress uprooted.[19] The presence and activity of the Franciscans is believed to be the cause of this riot. In one day, seventeen Spaniards were killed, and some four hundred servants were either killed or wounded.[19]

Killings of Friars[]

Another form of rebellion by the Maya and other indigenous groups against the Franciscans was the murder of missionaries themselves, often just two or three at a time, though in some instances many more. Described as martyrs, these men were picked off in twos or threes throughout the years of the missionary work all through Mexico.[20]

Success[]

While the term ‘success’ is a delicate word to use, considering the mass injustices of not only the Mayan people, but most if not all other indigenous groups that came in contact with the Spanish conquest in the sixteenth century, the conquests made by Spain were successful in terms of global achievement. It is to be lamented that the ancient way of life, not to mention religion, was drastically changed forever, but also important to note that Spain did indeed accomplish an enormous feat: a religious power from a small country in Europe that governed and maintained control of a vast area of land for several centuries. In history there is no equal achievement.[21]

Catholic missions in California[]

A view of Mission San Juan Capistrano in April 2005. At left is the façade of the first adobe church with its added espadaña; behind the campanario, or "bell wall" is the "Sacred Garden." The Mission has earned a reputation as the "Loveliest of the Franciscan Ruins."

Franciscans of the California missions donned gray habits, in contrast to the brown cassocks that are typically worn today.[22]

The Spanish missions in California (more simply referred to as the California Missions) comprise a series of religious outposts established by Spanish Catholics of the Franciscan Order between 1769 and 1823 to spread the Catholic faith among the local Native Americans. The missions represented the first major effort by Europeans to colonize the Pacific Coast region, and gave Spain a valuable toehold in the frontier land. The settlers introduced European livestock, fruits, vegetables, and industry into the California region; however, the Spanish occupation of California also brought with it serious negative consequences to the Native American populations with whom the missionaries came in contact. Today, the missions are among the state's oldest structures and the most-visited historic monuments.

Contemporary missions[]

Much contemporary Catholic missionary work has undergone profound change since the Second Vatican Council, and has become explicitly conscious of Social Justice issues and the dangers of cultural imperialism or economic exploitation disguised as religious conversion. Contemporary Christian missionaries argue that working for justice is a constitutive part of preaching the Gospel, and observe the principles of Inculturation in their missionary work.

List of Roman Catholic missionaries[]

- Gabriele Allegra, O.F.M. – Missionary to China to translate the Bible

- Francisco Álvares – Portuguese missionary to Ethiopia.

- Saint Amand

- José de Anchieta – Missionary in Brazil.

- Alexis Bachelot – Missionary to Hawaii.

- Alonzo de Barcena – Missionary and linguist.

- Carlos Filipe Ximenes Belo – Missionary in Mozambique.

- Jean-Rémy Bessieux – Missionary to Gabon and its first bishop.

- Luis de Bolaños – Missionary who started the Indian Reductions system in Paraguay.

- Libert H. Boeynaems – Missionary to Hawaii.

- Jean de Brébeuf – French Jesuit martyr in Canada who wrote Huron Carol.

- Luis Cancer – Missionary in Central America.

- Father Damien – Missionary to Hawaii known for working with the lepers.

- Louis William Valentine Dubourg – Missionary to the USA.

- Joseph Freinademetz – Nineteenth century canonized missionary to China.

- René Goupil – French missionary to what is now Canada.

- Évariste Régis Huc – French missionary in nineteenth century China.

- Isaac Jogues – French missionary to what is now Canada.

- John of Montecorvino – Franciscan missionary to China in Medieval times.

- Jordanus – Dominican missionary to India.

- Peter Richard Kenrick – Irish missionary to the USA.

- Eusebio Kino – Missionary to what is now the US Southwest.

- Fermín Lasuén – Founder of numerous missions in Baja California.

- Jacques Marquette – Missionary and explorer.

- Saint Ninian

- Marcos de Niza – French Franciscan missionary who accompanied Francisco Vásquez de Coronado.

- Roberto de Nobili – Jesuit missionary in India who learned Tamil and Sanskrit.

- Odoric of Pordenone – Franciscan missionary to China in Medieval times.

- Juan de Padilla – Franciscan who accompanied Coronado.

- Alexander de Rhodes – French Jesuit important to the history of Christianity in Vietnam.

Holy Ghost Fathers

- Matteo Ricci – Jesuit missionary in China.

- Junípero Serra – Founded the mission system of what is now the US state of California.

- Mother Teresa – Missionary to India.

- William of Rubruck – Franciscan missionary to the Mongols.

- Alessandro Valignano – Italian Jesuit who supervised missions in the Far East, particularly Japan.

- Francis Xavier – Jesuit missionary to India and Japan.

See also[]

- Catholicism in China

- List of Roman Catholic missionaries in China

Notes[]

- ↑ George H. Dunne, Generation of Giants, pp.86-88.

- ↑ Kenneth Scott, Christian Missions in China, p.83.

- ↑ Patricia Buckley Ebrey, The Cambridge Illustrated History of China. Cambridge, New York and Melbourne: Cambridge University Press, 1996. ISBN 0-521-43519-6. p. 212.

- ↑ John Parker, Windows into China: the Jesuits and their books, 1580-1730. Boston: Trustees of the Public Library of the City of Boston, 1978. p.25. ISBN 0890730504

- ↑ John Parker, Windows into China, p. 25.

- ↑ John Hobson, The Eastern origins of Western Civilization, pp. 194-195. ISBN 0521547245

- ↑ Habig 1945:342

- ↑ Clendinnen 1982

- ↑ Grahm 1998: 28

- ↑ Lee 1990:44

- ↑ Clendinnen 1982:45

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Clendinnen 1982: 33

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Clendinnen 1982: 29

- ↑ de Landa 1974: 74

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Clendinnen 1982: 30

- ↑ Clendinnen 1982: 31

- ↑ de Landa 1974: 60

- ↑ de Landa 1974: 61

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 de Landa 1974: 64

- ↑ Habig 1945: 335-6, 338

- ↑ Lee 1990: 42

- ↑ Kelsey, p. 18

References[]

Clendinnen, Inga (1982). "Disciplining the Indians: Franciscan Ideology and Missionary Violence in Sixteenth-Century Yucatán". Past and Present (Boston: Oxford University Press) 94: 27–48.

De Landa, Diego; Alfred M. Tozzer, trans. (1974). Relación de las cosas de Yucatán. Boston: Periodicals Service Company. ISBN 0-527-01245-9.

Graham, Elizabeth (1998). "Mission Archeology". Annual Review of Anthropology (Annual Reviews) 27: 25–62.

Habig, Marion A. (1945). "The Franciscan Provinces of Spanish North America [Concluded]". The Americas 1 (3): 330–44.

Lee, Antoinette J (1990). "Spanish Missions". APT Bulletin 22 (3): 42–54.